“Tonight, I do want to speak from the heart to the three million people who voted for Pat Buchanan for president. I will never forget you, or the honour you have done me. But I do believe, deep in my heart, that the right place for us to be now, in this presidential campaign, is right beside George Bush. This party is my home; this party is our home; and we’ve got to come home to it. And don’t let anyone tell you different.”

Pat Buchanan’s Kulturkampf speech (1992)

I'm not sentimental—I'm as romantic as you are. The idea, you know, is that the sentimental person thinks things will last—the romantic person has a desperate confidence that they won't.

Amory Blaine, This Side of Paradise (1920)

(I’m in the midst of an F. Scott Fitzgerald binge, and it activated the Nixon K-lines. I figured it would be dull if I served up two articles on Tricky Dick in a row, so to allow my readers some respite, I’ll focus on the career of one Patrick J. Buchanan.)

In order to understand Pat Buchanan, you need to have a basic familiarity with the motifs of The Great Gatsby. Wherein a western upstart fails to break into the incestuous eastern establishment, the struggle of the self-inventor forever distinct from the “splendours and miseries” enjoyed by that “American Aristocracy.”

There’s a reason why Pat begins his memoir Nixon’s White House Wars with an epigraph from that great American novel.

The book is both politically insightful for populists reeling from the half-assed Trump years, and emotionally affecting for romantics like us, who obstinately root for doomed reactionaries and lost causes. Buchanan remains one of the most charming ultras to have ever graced the American scene. In Nixon’s words, Pat was the only extremist he knew with a sense of humour.

And just as Nietzsche came to be the artist’s philosopher, so too was Nixon necessarily the poet’s president, packed full of pathos and psychic wounds, forever compelling if not commendable. For left-wingers, he was the poster boy for those post-protestant hang ups at the root of the evil of the rubes. An authoritarian personality in miniature ripped from Adorno’s imagination, an entertaining Beelzebub figure who could forever be psychoanalysed, in spite of his professed introversion.

Even with close friends, I don't believe in letting your hair down, confiding this and that and the other thing—saying, "Gee, I couldn't sleep ..." I believe you should keep your troubles to yourself. That's just the way I am. Some people are different. Some people think it's good therapy to sit with a close friend and, you know, just spill your guts ... [and] reveal their inner psyche—whether they were breast-fed or bottle-fed. Not me. No way.1

If Richard Nixon was indeed the Lucifer of the liberal mind, Buchanan made for a fine John Milton. Or as his friend Hunter Thompson described him, a “crazed Davy Crockett running around the parapets of Nixon’s Alamo — a martyr, to the bitter-end.”

Hunter S. Thompson, an inveterate pill-popping progressive, was also profoundly influenced by The Great Gatsby, to the point where as a younger writer he would copy whole passages from the novel, desperate to capture Fitzgerald’s rhythms as he developed his own distinctive voice. Despite their differences, he would become a buddy of Buchanan’s —remarking that “We disagree so violently on almost everything that it’s a real pleasure to drink with him.”

In response to Nixon’s famed artifice, Thompson anticipated Buchanan’s allusion to Fitzgerald.

“Nixon is a monument to all the bad genes and broken chromosomes that have queered the reality of the “American Dream.” Nixon is the Dorian Gray of our time, the twisted echo of Jay Gatsby.”2

The portrayal of Nixon-as-Gatsby was a lot more poignant than either Buchanan or Thompson probably intended it to be.

A young, postwar congressman like his perpetual antagonist John Kennedy, Nixon embodied a nouveau riche political sensibility. In his self-making mania, wonderfully outlined by Gary Wills, he resembled Gatsby and “sprang from his Platonic conception of himself.”

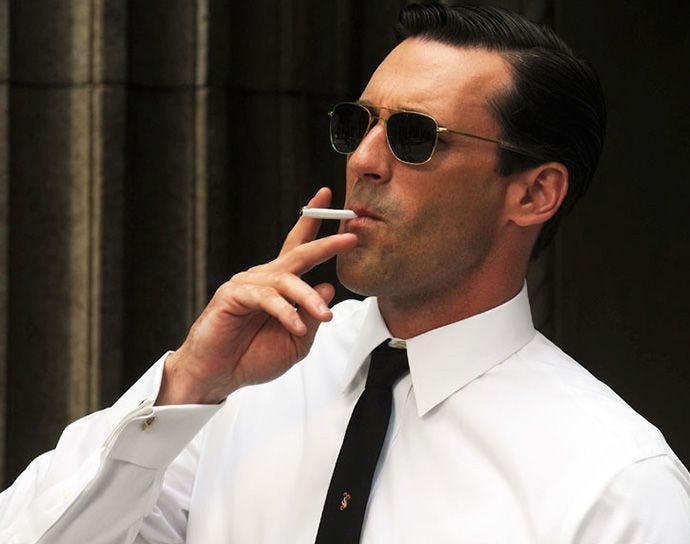

Matthew Weiner, the Jewish screenwriter behind Mad Men, said that his television show was about the process of “becoming white” in midcentury America. Dick Whitman steals Don Draper’s identity and the meek outsider becomes the consummate insider, moving from the Midwest to Madison Avenue, before that caste of cool-cats was obsoleted by the cultural revolution. The parallels to Fitzgerald and world-history should be obvious.

If one substitutes Gatsby’s jazz-age-pizzazz for Prez 37’s Californian-Quaker ethic, the parallels are as meaningful as the implications for conservatism in America (an oxymoron) are ominous. Nixon came in from the wilderness, shot through with the stench of what Wills identified as “a locker-room smell of spiritual athleticism.”

“The self-made man is the true American monster. The man who wants to make something outside himself—a chair, a poem, a million dollars—produces something. It can be praised or condemned; but it is “out there,” a thing wrought or won or subdued, apart from the self. The self-maker, self-improving, is always a construction in progress. The man’s product—his self—is never finished, not severed from him to stand on its own. He must ever be tinkering, improving, adjusting; starting over; fearful his product will get out of date, or rot in the storehouse…

“Nixon has this self-improving mania: the very choice of a framework for his book {Six Crises} reflects it… He can watch himself in action, and “improve” himself publicly, by the elocutionary method of that second-floor platform in Founders Hall. The book is a report card on the student’s progress. Mistakes in one crisis are corrected in the next, as if we were moving from semester to semester, from one course to another… He still lives through that rough day before the football game…

“One must not only try one’s best, but be conscious of trying, not enough to win, you must deserve the victory; deserve it by suffering for it. Easy wins are somehow tainted — the meaningless prizes of the brilliant… Nothing is being given {to} him on a silver platter. He is, Uriah-like, proud of his humble origin and great effort. No charisma here, or Kennedy charm; no decadent kid gloves…

“Nixon is President of the forgotten men, of those affluent displaced persons who howled at Wallace rallies, heartbroken, moneyed, without style—called by their moral code to Horatio Alger battle against the odds, then baffled by a cushy world admitting no heroics. These “rugged individuals” are tied together in live wires, endlessly multiplying, of compulsory technological interdependence. The Natty Bumppo of free enterprise did not want community in the first place; that would have been bad enough. But this mere entanglement, this parody of community, is even worse. Restless in such chains, our American frontiersman, grown of necessity flabby, feels he has betrayed a trust. And not only is he unfaithful, corrupted by affluence, by privilege without responsibility (supreme torture to a Calvinist); he must also stand by and watch while the code’s heretics rake in the good things—the slothful and undeserving, unwed welfare-mothers, the hippies screwing in parks, priests breaking the code by praising unmade selves.”3

Ever the Hegelian, Nixon’s psychology was animated by this existentialist angst, and a hunger for the chance to execute historically significant actions.

“To me, the unhappiest people in the world are those in the watering places, the international watering places like… the south coast of France and Newport and Palm Springs and Palm Beach; going to parties every night, playing golf every afternoon, then bridge. Drinking too much, talking too much, thinking too little. Retired. No purpose… They don’t know life. Because what makes life mean something is purpose. A goal. The battle. The struggle. Even if you don’t win it.”

To coin a phrase from Bob Dylan, were he not busy being born and reborn, subject to the pressures of politics and the grand verdict of History, Nixon would be busy dying. Left to rot in a New York law firm, “intellectually dead in two years and physically dead in four.”

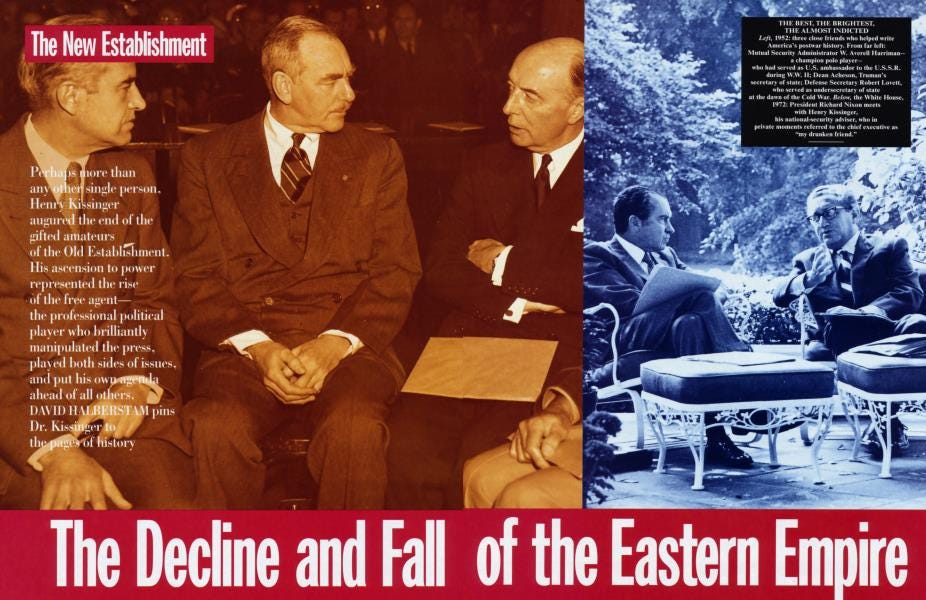

Similarly eccentric creatures were drawn into Nixon’s orbit. I’ve remarked on the Prussian flavour of his administration before, in the form of accomplices like Liddy, Haldeman, Ehrlichman and the soon-to-be-100 “Henry Kissinger… {who} haunted the outskirts of power in Kennedy’s day, but was too dour and Germanic for Camelot.”

These romantic resonances, reflecting those schizophrenic tensions subtly whirring within the minds of all real Americans, endeared Buchanan to his boss. Though higher-ups in the admin poked fun at Buchanan’s right-wing dogmatism (labeled “Strom Stuff” in private memos), Pat’s recollections are coloured by his deep loyalty to a leader who admittedly failed to deliver a conservative revolution. But the two bonded over their status as political refugees, perennially in Washington but never of Washington.4 Conservative outsiders besieging the walled city and nearly perishing in the unsuccessful process. In Fitzgerald’s words:

“I see now that this has been a story of the West, after all - Tom and Gatsby, Daisy and Jordan and I were all Westerners, and perhaps we possessed some deficiency in common which made us subtly unadaptable to Eastern life… Even when the East excited me most, even when I was most keenly aware of its superiority to the bored, sprawling, swollen towns beyond the Ohio, with their interminable inquisitions which spared only the children and the very old - even then it had always for me a quality of distortion.”

One could endlessly riff on the poetic presentation of the American Adam (in R.W.B. Lewis’s words) forever. But I only dwell on the Nixon leitmotif to reveal the severely emotional impulses behind Buchanan’s Nixon hagiographies. The battle betwixt East and West is a romantic construction of that past.

But the comparison to Jay Gatsby’s quixotic quest perhaps more importantly raises questions about the futility of reaction as a project, given the vicissitudes of time, as well as the darker side of the rightist’s tendency to hero-worship.

“I wouldn't ask too much of her,” I ventured. “You can't repeat the past.”

“Can't repeat the past?” he cried incredulously. “Why of course you can!”

“He looked around him wildly, as if the past were lurking here in the shadow of his house, just out of reach of his hand.

“I'm going to fix everything just the way it was before,” he said, nodding determinedly. “She'll see.”

This section is going to be bleak and maudlin. Allow an intermission, so I can preface this by saying that I don’t want to give off the impression that I dislike Pat Buchanan at all. I’d credit afternoons spent with the audiobook for his Where the Right Went Wrong for shaking me out of my movement-conservative stupor and awakening me to the threat of those pernicious neocons. It played an indispensable role in my radicalisation.

The book is subtitled “How Neoconservatives Subverted the Reagan Revolution and Hijacked the Bush Presidency.” And that cuts right to Buchanan’s fatal flaw. One reading through his corpus will quickly realise that he is very reticent to criticise his former bosses. After all, his acclaimed “Culture War” speech, his greatest rhetorical moment, was dedicated to an endorsement of his Bushite enemies.

While it is true that the neocons were more hawkish than Reagan, the Gipper’s Thomas-Paine tier “city-on-a-hill” rhetoric wasn’t far from their conception of the American Empire’s democratising purpose. The militantly anti-détente, anti-communist admin let those foxes into the henhouse in the place of realists like Kissinger. Mel Bradford got knifed under Reagan’s watch, and in an announcement speech early in the stretch, the seeds for NAFTA were sown.

“In his 1980 campaign announcement speech, Reagan proclaimed, “A developing closeness among Canada, Mexico, and the United States — a North American accord — would permit achievement in each country beyond that which I believe any of them, strong as they are, could accomplish in the absence of such cooperation…”5

In The Death of the West, Buchanan played the Spenglerian demographic doom-monger.

“Now 16% of the California electorate, Hispanics gave Gore the state with hundreds of thousands of votes to spare… With fifty-five electoral votes, California, the home state of Nixon and Reagan, has now become a killing field of the GOP.”

And yet one of the only other Reagan name-drops in that book was a simple allusion to an apocryphal warning he once issued, that “a country that cannot control its borders isn’t really a country anymore.”

By the standards of the early 2000s, that was bipartisan boilerplate. But looking past Reagan’s rhetoric, one finds a Republican patriarch who broke with the nativist tradition of men like Franklin, Hamilton and Coolidge to be completely rooked on the IRCA deal.

“Who killed the Reagan Coalition?” Buchanan asks. Well, Reagan did.

Maybe it was unreasonable to expect immigration hardliners to buck the party line as the Cold War was being won. But other populists of Buchanan’s vintage like Bob Whitaker were well aware of the Republican grift, and made hay of it in their missives.

“Republicans were happy in 1971 because the military was enormous and Nixon was defending the interests of business, and those are the only two things Republicans really care about. Working people’s kids were being bused and ethnic neighbourhoods were being broken up, but that didn’t matter any more to Republicans than it did to Norman Lear.

“The only people who were upset at liberal policy were Southerners and Northern ethnics. Lear had always hated white Southerners, but a Northern white person who deserted the liberal Democrats was even more evil in media eyes. The Archie Bunkers had been obedient little leftists under union supervision, but now that the unions were betraying them, they were leaving the Democrats and going to Wallace.

“And their names were not like “Archie Bunker.”6

We take the association of Republicanism and Conservatism for granted now, but that tryst was far from inevitable in the 1980s. For instance, Dixie was still very blue down-ballot until the Obama years. It was because of a half-century of conniving on the part of men like Buchanan, Phillips and Atwater that the modern electoral map came to be.

After the damage done to it, and the nation, through the New Deal era, the Grand Old Party was reduced to a weird WASPy thing, awkwardly thrust into the role of the loyal opposition, its cultural centre of gravity still very Yankee, believing in big-business über alles.

MAGA types came close to grasping the utter bankruptcy of the party around the Stop the Steal era, as the establishment(Tucker Carlson included) failed to provide the ex-president with the support needed to meaningfully contest the election. So Trump was left with only the crazies to help him — a position the man lingers in today. And that cypher Ron DeSantis has clearly been activated to get the culture warriors back onto the plantation. Not being an independently wealthy egoist who spits in the eyes of pro-lifers, they find it much easier to corral him into being a party man.

Buchanan’s fundamentally conservative wont for nostalgic flourishes, however beautiful, functions as a debilitating instinct. Russell Kirk had a similar problem, with his reactive, ponderous political persona. In Nietzsche’s words:

“As far as history serves life, we should wish to serve it. But there is a form of history that some feel driven to pursue that causes life to atrophy and deteriorate.”7

No, Buchanan’s honour lay not in his loyalty, but in his radicalism. Sam Francis, a southern man understandably disenchanted with the Washington duopoly — Anglo-Saxon Republicans and Ellis-Islander Democrats warring over appropriations — perfectly diagnosed this fault in his dear friend in the campaign autopsy “From Household To Nation.”

As Pedro Gonzalez, the self-styled Hispanic heir to Francis’s project has pointed out, although Rush Limbaugh cited the first half of the piece to explain the nascent Trump campaign’s appeal, the second section is more pregnant with meaning for populists in the present.

“If Buchanan has one major flaw as a spokesman for and an architect of the new Middle American political identity that transcends and synthesises both left and right, it is that he exhibits a proclivity to draw back from the implications of his own radicalism. This became evident in 1992, when he insisted on endorsing George Bush and even on campaigning for him… Buchanan, for all the radicalism of his ideas and campaign, remains deeply wedded to the Republican Party and to a conservative political label, and he tends to greet criticism of his deviations from conservative orthodoxy with affirmations of doctrine…

“Buchanan’s loyalty to the GOP is touching, especially since almost no Republican leader or conservative pundit has much good to say about him, and the loudest mouths for the “Big Tent” are always the first to try to push him out of it…

“I told him privately that he would be better off without all the hangers-on… who never fail to show up on the campaign doorstep to guzzle someone else’s liquor and pocket other people’s money. “These people are defunct,” I told him. “You don’t need them, and you’re better off without them. Go to New Hampshire and call yourself a patriot, a nationalist, an America Firster, but don’t even use the word ‘conservative.’ It doesn’t mean anything any more.”

Pat listened, but I can’t say he took my advice. By making his bed with the Republicans, then and today, he opens himself to charges that he’s not a “true” party man or a “true” conservative, constrains his chances for victory by the need to massage trunk-waving Republicans whose highest goal is to win elections, and only dilutes and deflects the radicalism of the message he and his Middle American Revolution have to offer.”8

Buchanan’s Reform-Party-pivot came too late, and proved starry-eyed without Trumpian wealth or Q-Scores. And here again, at last, we arrive at the futility of Buchanan’s project. Like Mircea Eliade’s archaic man, Buchanan ritualistically partakes in republican hierophanies — only the sacred past fails to materially manifest, come a victorious election cycle. Wiping away its Gatsbyite outsider affectation, the party only delivers Progress driving the speed limit.

The haunting quality of Gatsby is that Fitzgerald paints that historical way of being, as not only mentally inescapable, but materially irreversible. This is a self-evident challenge to any conservative program.

“I thought of Gatsby’s wonder when he first picked out the green light at the end of Daisy’s dock. He had come a long way to this blue lawn, and his dream must have seemed so close that he could hardly fail to grasp it. He did not know that it was already behind him, somewhere back in that vast obscurity beyond the city, where the dark fields of the republic rolled on under the night.

Gatsby believed in the green light, the orgiastic future that year by year recedes before us. It eluded us then, but that’s no matter — tomorrow we will run faster, stretch out our arms further… And one fine morning —”

If one judges him only by his political career aside from his revolutionary polemics, Buchanan will go down in history as a conservative, rather than a radical. Beating on the neoconservatives and yelling “Stop!” at Progress’s currents like those faithful followers of Bill Buckley’s encyclicals. A partisan crusader borne back ceaselessly into his mission, the impossible restoration of an unreconstructable past.

http://www.jewishworldreview.com/bob/greene040802.asp

Hunter S. Thompson, “Fear and Loathing in America”

Garry Wills, “Nixon Agonistes”

Sure, Buchanan was born there, but he earned his stripes at a Missouri newspaper, and his sincerely counter-revolutionary Catholic background always set him apart from his peers.

https://www.revolver.news/2021/04/reaganism-was-just-globalism-with-a-conservative-face/

https://identitydixie.com/2019/11/17/archie-bunker-and-george-wallace/

Paul Gottfried, “Revisions and Dissents”

https://chroniclesmagazine.org/web/from-household-to-nation/

DM