Kondylis's Konservativismus: The Cure for Kirkian Cuckservatism

Two historians of the Right examined

“We don’t win anymore.”

Donald Trump, “Announcement Speech”

“CONSERVATIVE, n. A statesman who is enamored of existing evils, as distinguished from the Liberal, who wishes to replace them with others.”

Ambrose Bierce, “The Devil’s Dictionary”

“As the American social order becomes increasingly identified with postmodern tendencies — for example, feminism, secularism, and governmentally mandated social equality — it may grow ever harder for historical conservatives to sustain the argument that Russell Kirk offers…”

Paul Gottfried, “The Search for Historical Meaning”

“Here there was no fiery individualism, no trace of populism or radicalism to upset the ruling classes or the liberal intellectual Establishment. Here at last was a Rightist with whom liberals, while not exactly agreeing, could engage in a cozy dialogue.”

Murray Rothbard, “The Betrayal of the American Right”1

I know I shouldn’t be spilling ink on the subject of historicism and the Right again, given the delays already afflicting my series on “Paul Gottfried and the Crisis of the German Right” — specifically the Hegel entry which will be done soon — but it is somewhat important to outline themes that will reemerge when I get to writing about the relationship between Gottfried and Kondylis. A historicist reconstruction of the nature of a vitalist Right will also be critical to the message of the blog as a whole.

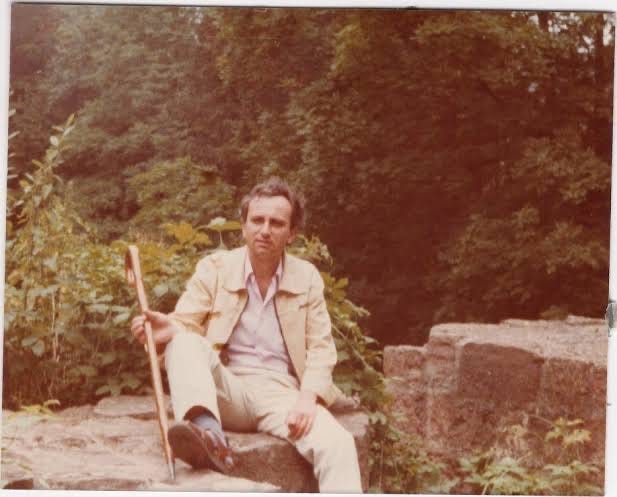

At the outset, I was a big Russell Kirk fan.

He praised icons of the old right like John C. Calhoun and broke from his apolitical stance to back Pat Buchanan in ‘92. His critiques of the libertarian way-of-being from the right have aged very well. He took glorious shots at the neoconservative cartel monopolising the marketplace for conservative ideas throughout the 1990s, boldly declaring that they “mistook Tel Aviv for the capital of the United States.” He perceptively observed that, in South Africa, the issue was not black and white but a question of “how to govern tolerably a society composed of several races, among which only a minority is civilised.” His opposition to mob-rule on the dark continent was a far cry from the mass-democratic bromides excreted by modern conservatives today.

On the surface, one sees a traditionalist good on the issues, with a poetic talent for expressing them.

The Conservative Mind remains a classic text on the right-wing tradition in America, elegantly illustrating a reactionary current in the American mind too often neglected or disparaged by the court historians. To his credit, he was of a conservative generation that praised figures like John Randolph of Roanoke, rather than denouncing them as for their party affiliations — revealing the “real racists.” That being said, the flaws in Kirk’s literary approach have been utterly deleterious for the American right’s self-conception.

From Russell Kirk to Charlie Kirk:

One of my better finds when trawling through the secondhand bookstores of Sydney was a well-preserved copy of Russell Kirk’s Redeeming the Time. The book, focused on the issues facing America in the 1990s, was described as “at once elegant in style, gracious in tone, and absolutely serious in thought.” The source of that praise? The infamous David Frum.

It was a big red flag for me that the spineless hatchet-man who helped with purging the paleocons saw something of value in Kirk’s writings.

“[The Conservative Mind] is, in important respects, the twentieth century's own version of the Reflections on the Revolution in France... [Kirk] was an artist, a visionary, almost a prophet."

On paper, Kirk was far from his neocon fans. We have touched on his anti-Zionism, his Buchananism, and even his affinity for Southern Conservatism (he did write his first book on John Randolph of Roanoke - that foe of “king numbers,” after all.)

The reason why neocons like Frum can stomach Kirk and not a more racy polemicist like Sam Francis, beyond the racial elephant in the room, is that Kirk’s reactionary musings instil in their reader an anticipation of defeat. Frum can break intellectual bread with Kirk for the loser’s mindset that they share.

This stems from Kirk’s reactionary disposition, downstream of which are the flaws in his conception of what the American right-wing tradition was and is.

“Kirk’s 1953 book The Conservative Mind gave {movement } conservative ideology a historical sweep and intellectual grandeur. Kirk was not the right’s creative Dr. Johnson but rather its Boswell — the man who brought conservative ideas into mainstream thought. Kirk proposed “six canons of conservative thought” that tacitly fused Hayek and Weave… {a belief in} divine rule, the connection between private property and freedom, and the value of order, tradition and classes. Conservatives opposed social engineering, efforts to achieve “equality of condition” and the supposition that all change was positive.”

His ideology could be uncharitably described as a cold-war contrivance. His a synthetic fusionism bound together a self-contradicting coalition with a reactionary mood. This led to the development of a calcifying mindset at the top, and thought-leaders utterly afraid of a victory by impure means.

“I am a conservative. Quite possibly I am on the losing side; often I think so. Yet, out of a curious perversity I had rather lose with Socrates, let us say, than win with Lenin.”2

A noble sentiment — my own sympathy for the romance of lost causes goes without saying — but an outlook that invites defeat in politics. There exists a clear contrast between this attitude and the Right-Wing Leninism pushed by a Steve Bannon or a Murray Rothbard.

Furthermore, Kirk’s Burkean focus on the persistence of national traditions, stressing their ability to adapt to revolutionary demands, was used to illustrate an artificial continuity between the ancien regime and modern America.

This is why the neocons still read Kirk.

The Greek-Life Alternative:

"To be conservative… is to prefer the familiar to the unknown, to prefer the tried to the untried, fact to mystery, the actual to the possible, the limited to the unbounded, the near to the distant, the sufficient to the superabundant, the convenient to the perfect, present laughter to utopian bliss."

Michael Oakeshott, “On Being Conservative”

“Conservatives" who define their "conservatism" as an attitude or mood tend to describe it in the most intellectually sophisticated way possible, especially since these are often more or less idealized self-portraits.”

Panagiotis Kondylis, “Konservativismus: Geschichtlicher Gehalt und Untergang”

But how then, should conservatives think of themselves?

The answer lies in the works of Panagiotis Kondylis.

I wish to place Kondylis into a textual conversation with Kirk, with natural implications for the strategy and self-conception of the western right going forward. An analysis of Konservativismus reveals a much healthier vision of what the western right once was, and what it can be again.

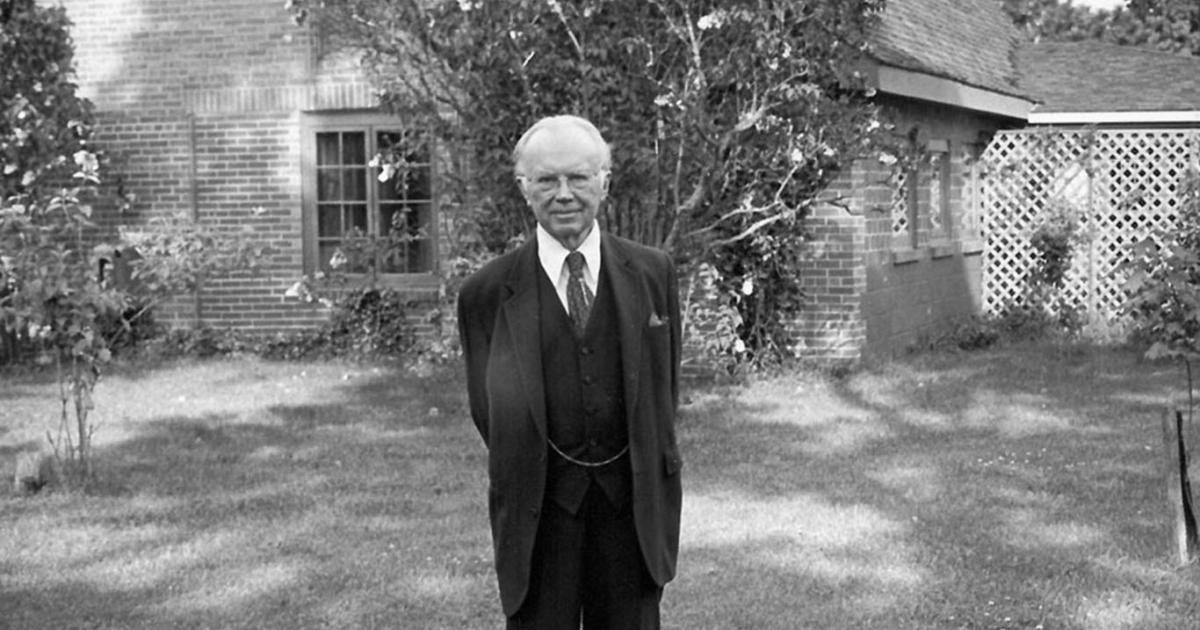

Kondylis was a Germanophone Greek Marxist with an incisive, utterly unromantic polemological style — interrogating concepts as they were used in historical struggles for power, and dismissing the flattering self-representations of his subjects.

He wished to focus on “the actual events in history, {which} take place beyond the polemical slogans, although the promoters and users of these slogans believe in a necessary relationship of these slogans to historical events.”

Though his thought was derived “from materialism and Marxism… his polemic against conservatism bears the marks of a Hegelian historicism that opens up his work to bourgeois-liberal, if not reactionary, readings.”3 This is why his books were useful to right-wing critics of American conservatism like Paul Gottfried. This article follows in that tradition.

Konservativismus teased out two quintessentially dissident right truths.

Firstly, Conservatism is a doctrine, not a disposition. Kondylis contests the idea that “Conservatism is the view that the existing socio-political and economic order is the result of a historical development, but that it does not exclude minor and cautious reforms and improvements.”

Following from this, revolutionary methods are entirely in line with the right-wing tradition when under the bootheel of the Jacobins. Kondylis observed that conservatives had handicapped themselves with their own self-mythologising.

“It is indeed worth noting how the central topoi of conservative self-understanding and conservative self-representation have found their way into conservatism as perceived by non-conservatives as well. Thus, the almost axiomatic thesis put forward by all sides that conservatism arose as a reaction against the French Revolution or already against the Enlightenment reflects, albeit indirectly and distortedly, the conservative view of the nature of conservative man, according to which he is never the first to seek or start a quarrel, but on the contrary is the peace- loving and peace-ready man par excellence, since he lives in accordance with the natural or divine commandment of pious preservation; Only the active violation of this commandment on the part of others unleashes an urge to action in him. However, it is not easy to see why this - if we disregard the value judgments connected with it - should be a specific feature of conservative behavior. No man reacts hostilely to the stimuli of the environment as long as no obstacle stands in the way of his self-preservation or his striving for power.”

But the apologia was self-defeating. This reactionary learned helplessness generated the very victimhood-mentality American conservatives pretend to despise.

The second point Kondylis drives home is the distinction between old Europe/America and the current regimes running both continents. In his radically historicist style, he itemised time-bound political systems, recognising the substantive distinctions between successive social orders.

In fracturing the continuity constructed by the centre-right between the old regime and the new, Kondylis unveiled the nightmarish nature of our mass-democracies in his other works — though he maintained his uniquely nihilistic, non-normative style.

One’s tactics must necessarily change with the loss of power. On the bright side, American conservatives are starting to wake up to the institutional hostility directed against them.

Russell Kirk confused means with ends4, habits developed in a position of power with the essential character of the right. He left his students intellectually ill-equipped to respond as their country slipped out of their hands.

Now for the real history of conservatism.

A True Conservative’s Way-of-Being:

“Conservatism and activism do not form an irreconcilable opposition, if one only pays attention to the historical reality and does not tend to take at face value the self-representation of the conservatives, which is subsequently designed for polemical purposes."

Panagiotis Kondylis, “Konservativismus: Geschichtlicher Gehalt und Untergang”

From a critical, albeit non-normative left-wing perspective, Kondylis beheld a vital reactionary movement.

“Long before they were threatened by the revolution, the most important members of the upper classes of civil society led a very active life, whose goal was not least the improvement of their own position of power by gaining office and wealth…”

Observing historical realities and not conservative self-representations from his Marxist perspective, Kondylis ruthlessly critiqued the concept of an inactive conservatism.

“{Peter} Viereck (Conservatism Revisited) also arrives at a banality… one should change cautiously without upsetting the basis of the existing. Viereck would probably be disappointed to hear that it was precisely this principle or advice that the Soviet leadership, for example, had imposed on the Czechoslovak reformers as a 1968 condition for refraining from military action.”

In Kondylis’s eyes, any definition of conservatism expansive enough to encompass the Soviet vanguard was too broad. The “psychological-anthropological interpretation” of conservatism made it a pointlessly vague, and inaccurate label.

“The psychological-anthropological interpretation of conservatism may be countered in general that neither the urge to preserve nor the urge to overthrow characterizes human behavior in general, but the endeavor to preserve or to increase one's own power; to this supreme purpose, sometimes preservation, sometimes overthrow.”

A reactionary attitude was a product of one’s social position, rather than ironclad principles.

“It is not a given psychological-anthropological disposition that is at work here, but rather the relative position, i.e. the concrete position of power of the respective subjects, remains decisive. Only in this perspective it becomes understandable why the victorious revolutionary changes overnight into a zealous defender of the existing, or why the defeated conservative or the conservative fearing defeat lies with violence or even uses it openly. There is no reason to assume that this reorientation of political behavior costs the conservative groups more self- conquest than might be the case with other social forces. Feudal right of resistance and "tyrannicide," fraternization and dictatorship are, as we shall see, historically documented and by no means atypical forms of conservative activism.”

You must be the vital reactionary the Bolsheviks imagine you to be.

The Right’s Flight from the Political:

Carl Schmitt was a profound influence on the works of Kondylis via his student Reinhart Koselleck. Schmitt’s fundamental insight was the antagonistic nature of the Political, reducing political questions to battles between friends and enemies.

Kondylis’s own view, articulated in works like Power and Decision, was that “the infinite variety of human perceptions, beliefs, ideologies, i.e. world-views, are nothing more than an effort to give personal interests a normative form and an objective character.”

Midcentury conservatives, many poetically inclined men like Kirk or Eliot, painted themselves as apolitical wanderers through the world, shying away from conflicts.

“As a rule, the more a "conservatism" is apolitical, the more irrefutable… it appears. Preferably, the apolitical takes the most sublimated form, namely that of a metaphysical-poetic flight of fancy. Thus, the conservative soul is sung about and painted in the deeper harmony of the universe, as well as the serene, erotic and musical nature of this soul, which is averse to violence, fear, and trust, whether from the revolutionary or the reactionary side. A conservative man, "who knows himself secure in the order of being and sees in all images the image of the One'', believes absolutely in God and not only feels free of any ideology (!!), but is also "a stranger in the modern parliaments, in the halls of mass meetings, in the leafy forest of the press, in the world of today in general".”

The stupidity of this sanitised self portrait should be apparent — you will not win a political struggle if all you want is to grill.

In critiquing libertarians, whom Kirk ignominiously dubbed “chirping secretaries,” he unveiled his own romantic, apolitical conception of a conservative’s worldview.

“The libertarian thinks that this world is chiefly a stage for the swaggering ego; the conservative finds himself instead a pilgrim in a realm of mystery and wonder, where duty, discipline, and sacrifice are required–and where the reward is that love which passeth all understanding.”5

To Kirk, conservatives reluctantly entered into politics as a reactive gesture, an attitude Kondylis satirised with glee:

“The apolitical tries to establish some kind of relation to the earthly reality… sometimes longingly remembering the pre-state reality, the ideal world of the small agricultural communities, where the individual allegedly possessed the cautious security in the bosom of the family and religion… Christianity and modernity thus prove to be incompatible with each other; and if a conservative of such stature somehow participates in politics, it is only in order to use his Christian attitude to defend against {it}.”

Kondylis’s revisionism also sheds light on Kirk’s American context. For all of our attacks on movement conservatism, they rarely acted in line with their apolitical image.

In the neoconservative era they were certainly no strangers to expanding the state. The libertarian idea of an overly-active conservative movement is closer to the truth than the Populist Inc caricature of a lethargic ideology.

Contrary to that image of a centre right that never fights, they have a track record of playing to win, much more so than Trump — who rewarded his enemies and allowed his friends to be punished6.

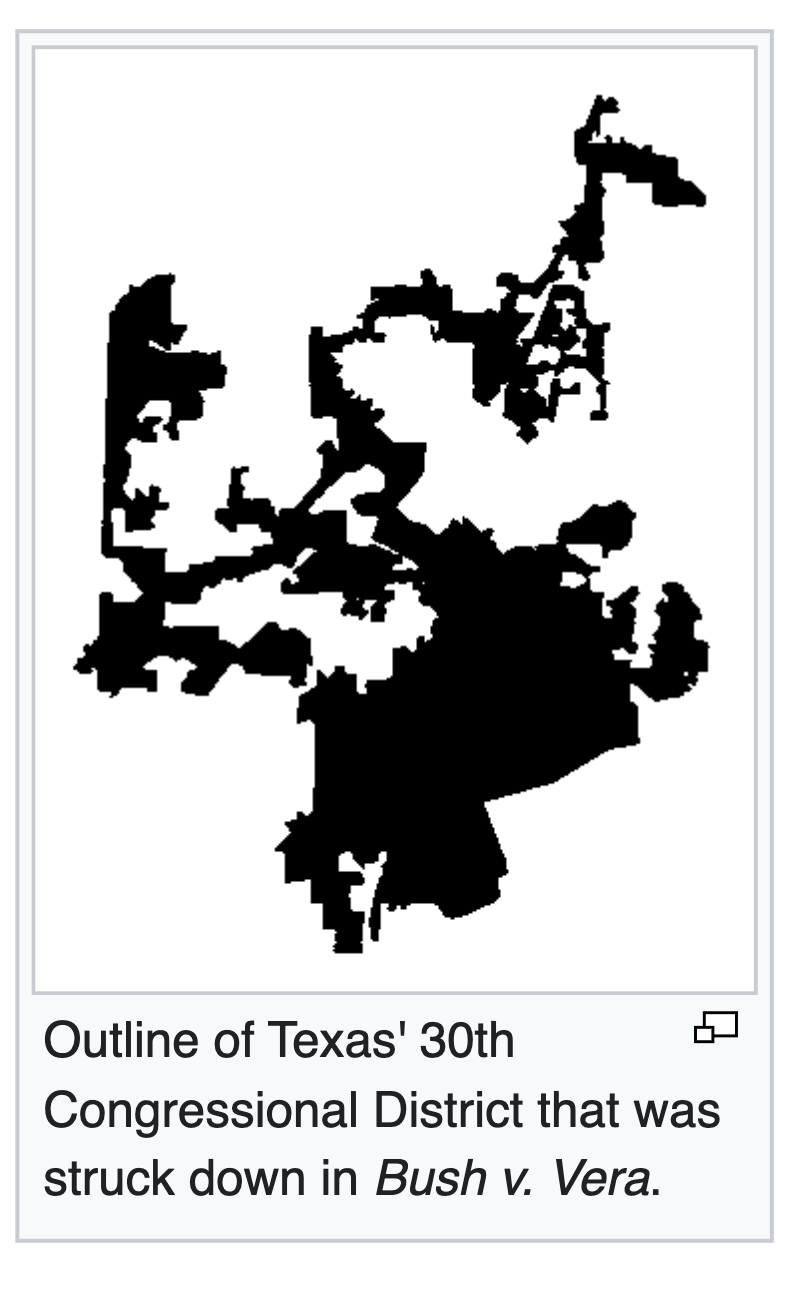

Allan Lichtman’s “White Protestant Nation” provides the history of a truly vigorous political persuasion, not the idle smattering of nostalgic intellectuals captured by Kirk in “The Conservative Mind.” To Lichtman, the right’s co-ordination of out-of-state volunteers in the Bush v Gore election contest was proof positive that “at the turn of the twenty-first century, the right was better organised than the left, more passionate, and more devoted to winning control over government.”

It would be more accurate to suggest neocons fight for their own people, and have historically done so. The trouble comes when good hearted conservatives internalise that imaginary tendency towards inaction now expected of them.

“In portraying themselves as the victims of history, the European Right were able to portray themselves as victims, but this did nothing to advance their aims, only romanticizing their historiography.”

An Imagined Continuity:

“It is possible today to be a self-described Kirkian without having any political opinions except that global democracy is swell and that George W. Bush is a Kirkian president. Most Kirkians now express these views with dismal regularity.”

Paul Gottfried, “How Russell Kirk (And The Right) Went Wrong”

Kondylis’s historicism also importantly shattered any imagined continuities between old America and the GAE. His theoretical distinction between 19th century liberalism and the 20th century’s mass-democratic regimes is a radical concept to internalise, intuitive to libertarians who want to wash their hands of the contemporary American experiment.

Russell Kirk, by contrast, used his view of conservatism as a disposition to contrive a continuity between the new American regime and the old. Conservatives now bizarrely feel obligated to defend a mass-democratic, anti-conservative system of government, because of that artificial continuity he promoted. They are unable to act politically with a clear image of their social goals, historical roots and national destiny.

A key task of the dissident right must be to smash that notion — driving a wedge between western subjects and their states. To be unreconstructed is to be a recalcitrant rebel under an occupation government.

“Many conservatives continue to indulge an outmoded habit of the anti-Communist Right: glorifying present-day political America as the embodiment of an ancient tradition seen in mortal combat with its enemies…

“Kirk purported to be showing how the American government and American culture took form from a cultural mix produced by Rome, Athens, and Jerusalem. Observe that Kirk insisted on such continuity even though the U.S. was then clearly on its way to becoming a self-identified multicultural society overseen by a post-Christian managerial elite…

“Instead of imagining that the old America was "enduring" in the present one, Kirk and his fellow-archaic conservatives should have been calling attention to a successor regime, whose sources are Washington-New York-Hollywood.”7

“Kirk's major contribution to the American Right, Wes assures us, was as a literary figure and cultural critic. Accordingly, he never felt comfortable with the paleoconservatives, whom he considered politicised reactionaries and—as Kirk also considered the neoconservatives—obsessed ideologues.”

“For the most part Kirk could be counted on to end his work optimistically and to stress the traditionalist sources of what by then was a radically changed America.

“He did not allow himself to get drawn into embarrassing political fights, e.g., about immigration, anti-white racism enforced by our government and media, and the bloated social-engineering bureaucracies that are poisoning our civil society.

“The anti-ideologue Kirk ducked those wars that necessarily concern those on the right who notice the political culture…

“A glorification of imaginary or exaggerated continuity was not the only impulse in the postwar conservative movement. But it was there from the beginning.

And, for better or worse, Kirk… helped nurture that belief.”

Some of these errors can be chalked up to Kirk’s polemical pandering to a wide audience. Vague bromides about your mental disposition are more palatable than specifying outright the social order you wish to return to — especially in a society as pluralistic as the American one.

Kondylis recognised the inherently liberal traits that characterised popular American “conservatism”:

“The American "conservatism" of all things provides us with the best insight into contemporary conservatism in its caricature-like nature. The appeal of the American "conservatives" fighting against the welfare state to aristocratic ideals of life, as well as their condemnation of indiscriminate individualism and economism, sounds most strange, even comical, in a nation that arose and grew up under the sign of pure liberalism (in the European sense) - if there ever was such a thing - and without having to fight for the victory of this liberalism against a native ancien regime. A real, i.e., standish and anti-liberal conservative attitude could not develop here out of agrarian life, which took place all too much on isolated farms run by individual farmers, than it could on isolated farms run by individual farmers to produce a sense of "community" and "tradition," nor from religious life, whose prevailing Protestant tendency favored an extreme individualism associated with strong activist moments; nor did old wealth exert a decisive influence on social life, so that the main goal of its owners, who had to protect themselves from the much more rapidly accumulating wealth, was to protect the people from the danger of the "socialist" tendency. the rapidly accumulating wealth of the nouveaux riches and the corporations, was to adapt to the mores dictated by the latter rather than to find their own way. Finally, it was precisely individualism and economism that became traditions, which, under the later influence of mass consumption, developed in the eudamonistic direction, thus at least partially incorporating their original puritanical features. Under these circumstances, a conscious socio-political tendency, which deserves the name "conservative" only if we mean by it the defense of the existing social and economic rules of the game, could only emerge as a partisanship for the threatened laissez-faire principle (and not as a rejection of it, as happened in Europe). The threat emerged on the American horizon in the last decades of the nineteenth century in the form of the idea of welfare, which partly replaced the laissez-faire principle, which until then had been synonymous with political economy per se and often underpinned by social Darwinist arguments. It was precisely at this time that "conservative"-minded judges issued famous rulings that sought to prevent the state from interfering in economic life, whether to curtail property rights or to regulate labor relations in the welfare state sense.”

He was keenly aware of the incoherence of American conservatism.

“It is not surprising that the American "conservatives" must remain stuck in the same basic contradiction as their European counterparts. They reject the ultimate social and cultural consequences of a system whose economic and political axes they endorse, or they are unwilling or unable to come to terms with. they do not want to or cannot come to terms with the fact that - formulated in Hegelian terms - the basic order preferred by them must produce its own negation out of its own shock, and they are anxious to offer up old ideas and older, partly fear-dead attitudes to life as a counterweight against the latest development in the direction of a consuming mass democracy. If, however, on (Western) European soil this basic contradiction is sometimes concealed or rather glossed over by the fact that the aforementioned ideas have deep native roots and, in the worst case, need only be revived (even on paper), not invented or imported, in the U.S.A. the great sore point of contemporary "conservatism" appears openly because here national tradition provides hardly any ideological or social points of reference for the construction of a "conservative" society.”

I don’t wish to get too far ahead of myself, but this is precisely Paul Gottfried’s critique of the American Right.

“1) there is no social base for the conservative movement in America;

2) without a social base, the conservative movement had to resort to universal values in order to connect itself to the current form of life;

3) these universal values are inherently anti-traditional and therefore anti-conservative.”8

Kirk would rather “lose with Socrates” than “win with Lenin.” And so his traditionalist ideas were muscled out of the public sphere. Not all ideas are consequential. Gottfried and Francis, learning from historicist Germans, recognise the need for elite patronage and a social base to work from.

To Kondylis, “the memory of these facts should have made it understandable why the contemporary American "conservatives" went to Europe (and to the past) to find the "higher" ideas and values they needed, thereby setting themselves the highly unconservative task of inventing a tradition that would give bodily existence to their a priori fixed doctrines.”

This synthetic tradition, a harmless persuasion, foreshadowed the total collapse of the fusionist alliance following the dissolution of their Communist common enemies. American Conservatism dedicated itself to rationalising the interests of a non-conservative business class.

“The ghostly character of American conservatism, one might say, is evident from the fact, already emphasized by many observers, that the ideals propagated by its representatives do not correspond in any way to the prevailing world of ideas of the American business class, which thinks in an economistic and expediently rational way and, moreover, tends to set aside fundamental objections to big government, provided and as soon as the latter makes policy in its interests…

“{Clinton} Rossiter now expects a kind of inner conversion of businessmen, so that they could become the natural bearers of conservatism; to this end, they would have to detach themselves from economism, which is in fact an inverted Marxism, and, without abandoning the American practical and individualistic spirit, they would have to develop their own activity subordinate to certain values and a sense of community. The ,,conservative" did not at any time question the predominance of profit as a motive, but on the other hand he wanted it to be understood as something intrinsic and to be kept within "destructive", socially acceptable limits.”

In observing this, Kondylis recognised the lack of continuity between classical conservatism and the modern right.

“The "conservatives" who call or called themselves "conservatives" had little in common with those who originally bore this name, and filled the old conservative commonplaces, insofar as they are still used, with essentially new content. Hardly any of today's "conservatives" seek to undermine the fundamental separation of state and society (just the opposite is the case), hardly any question equality before the law or "human rights" (no less than that), and hardly any would think of abolishing the boundaries between the private and the public or between legality and morality, which were first established in the struggle against the societas civilis; Even the relations between the individual and the collective, or questions such as the freedom of intellectual creation, are as a rule understood by today's "conservatives" in a completely different way than by their alleged predecessors.”

With the Americanisation of the west, these ideological quirks would manifest elsewhere. Artificial Kirkian continuities were enshrined.

Kirk’s denunciations of the “hubris of the ruthless innovator” inadvertently marshalled conservatives to the defence of a profoundly non-conservative social order. His fans crusading like Jacobins in the Middle East was the tragic result.

Wither the Right?

“Canonical conservative thinkers such as Burke, de Maistre, Cortés, or Bonald, often drew on the ideal of an essentially medieval hierarchical society defended by landed aristocrats and their intellectual supporters. The conservative revolution placed little hope in a reactionary return to the past. Such visions failed to appreciate the truly radical challenges and opportunities presented by industrial modernity, and had very limited traction in an age of mass democracy.”

“Radical Conservatism and Global Order: International Theory and the New Right”

“The passing of conservatism, then, cannot be mourned. Like any species that slips into the evolutionary twilight, it was unable to respond to the challenges it encountered, and good riddance to it.”

Sam Francis, “The Survival Issue”

To Kondylis, western conservatism was a dead ideology walking, the concept kept alive for polemical purposes.

“Conservatism as a concrete historical phenomenon that was accompanied by a firmly defined ideology is… dead and buried. It is simply nonsensical to call contemporary Western political programs, parties or governments "conservative", which are committed to technological progress, social mobility and thus to the modern principle of the feasibility of the world, and thus, despite all traditional moralizing rhetoric, call for a development that has initiated as yet unforeseeable transformations in human history and will perhaps not even stop at the biological substance of the species.”

“Such language has nevertheless become indispensable for polemical reasons: it is needed both by orthodox liberalism, which wants to distinguish itself from the mass-democratic and welfare-state tendencies of "left-liberalism," and by the left of all shades, which in its endeavor to monopolize "true" progress for itself can think of no worse accusation against its enemies than that of "conservatism" and "reaction." The actual events in history, however, take place beyond the polemical slogans, although the promoters and users of these slogans believe in a necessary relationship of these slogans to historical events.”

The western right festered in a conceptual quagmire after the Cold War, a persuasion without a purpose. Kirk’s paean to the “poets of permanence” intellectually incapacitated a generation. This conception of conservatism as a disposition, combined with his portrait of a continuity between Old America and New, led Kirkism to be lethal. Too many good reactionaries defanged themselves and backed the plays of their enemies because they believed in their own bullshit.

The political soldier needs Kirk’s reactionary heart, in sync with Kondylis’s polemical fury.

As good as he could be on those central issues of identity and culture, his defeatist mindset was a generationally bad influence on the right. His elegant prose and based opinions did not prevent him from falling on the wrong side of that fundamental division between the vigorous post-Trump New Right and its movement-conservative enemies. The will to win, and the ironclad belief that we will.

That belief in an inevitable victory was essential to the spirit of 2016, and Kirk simply lacked it.

My verdict is that Russell Kirk was a loser, and that his books taught other young rightists to be losers too. His poetic tracts seduced an entire generation with the romance of defeat.

Yet still, in my eyes, he remains the most beautiful loser of them all.

It is, on the whole, a mixed bag of a book. Particularly when he indicts Kirk’s best contribution to the American Right:

“Kirk also succeeded in altering our historical pantheon of heroes. Mencken, Nock, Thoreau, Jefferson, Paine, and Garrison were condemned as rationalists, atheists, or anarchists, and were replaced by such reactionaries and antilibertarians as Burke, Metternich, De Maistre, or Alexander Hamilton.”

This is also inaccurate. Kirk consciously favoured the pessimistic John Adams to the nationalistic Alexander Hamilton. He also wrote his first book on that aristocratic libertarian hero John Randolph of Roanoke. Unsurprising, considering Kirk worshiped the anglophile TS Eliot, who saw in the American South superior “chances for the re-establishment of a native culture… than in New England.”

Addressing his Virginian audience, Eliot observed that:

“You are farther away from New York; you have been less industrialized and less invaded by foreign races; and you have a more opulent soil.”

From Kirk’s “Why I Am a Conservative”

https://www.greeknewsagenda.gr/interviews/rethinking-greece/6088-rethinking-greece-angelos-chryssogelos-and-georgios-antoniadis-on-greek-conservatisme

Community-college dropout Youtuber John Doyle intuitively gets this, when he talks about right-wingers having an allegiance to procedural means rather than concrete political ends.

https://theimaginativeconservative.org/2010/07/russell-kirk-conservatives-and-libertarians.html

https://amgreatness.com/2021/01/17/rewarding-enemies-punishing-friends/

https://web.archive.org/web/20130317074223/http://www.vdare.com/articles/how-russell-kirk-and-the-right-went-wrong

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/315743448_Introduction_to_Symposium_Continuity_or_Creation_American_Conservatism_in_Paul_Gottfried's_Conservatism_in_America

Are you aware of the Sydney Traditionalist Forum?