(It is the anniversary of Nixon’s death in American time, as I write this.)

“I know that after my death a pile of rubbish will be heaped on my grave, but the wind of History will sooner or later sweep it away.”

Joseph Stalin

“Kissinger was only one of the many historians who suddenly came to see Nixon as more than the sum of his many squalid parts. He seemed to be saying that History will not have to absolve Nixon, because he has already done it himself in a massive act of will and crazed arrogance that already ranks him supreme, along with other Nietzschean supermen like Hitler, Jesus, Bismarck and the Emperor Hirohito. These revisionists have catapulted Nixon to the status of an American Caesar, claiming that when the definitive history of the 20th century is written, no other president will come close to Nixon in stature.”

Hunter S. Thompson, “He Was a Crook”

Well, count me among those revisionists Mr. Thompson!

For one can’t understand the Byzantine character of the Nixonian moment without grasping the subtle, teutonic notes in his statesmanship. Although my writings have taken on a Wallaceite tone in recent months, I remain a Nixon partisan.

First, let’s set the scene. The sixties bore witness to Rooseveltian liberalism’s death agonies. The first Republican in a decade entered the Oval Office with a narrow popular-vote plurality. He was the first president to take office facing two hostile chambers of Congress since Zachary Taylor in 1848. It was a time of total war. Grok the standoff between A.G. John Mitchell and the hippie hordes on Mayday, 1971, as described by the activist Caleb Rossiter:

“With unbridled delight at getting a chance to communicate with one of the enemy… we screamed “Fuck you Mitchell, fuck you Mitchell,” and threw at him whatever debris we could find. He looked down calmly from the railing, which was far too high for our missiles, holding his pipe, and with great deliberation gave us the finger right back.”1

With a nigh-unprecedented intensification of divisions within the American polity, the subsequent causal nexus spawned an administration that became the flashpoint for a burgeoning reaction to the excesses of the revolutions of the 1960s. With the empire overextended abroad, and anarchy at home, corrections were in order.

The Germanic idea of a responsibility to history figured prominently in the Nixonian mind. Max Weber summarised this solemn duty best:

“The Danes, Swiss, Norwegians, and Dutch will not be held responsible by future generations, and especially not by our own descendants, for allowing, without a fight, world power to be partitioned between the decrees of Russian officials on the one hand and the conventions of Anglo-Saxon ‘society’ — perhaps with a dash of Latin raison thrown in — on the other. The division of world power ultimately means the control of the nature of future culture. Future generations will hold us responsible in these matters, and rightly so, for we are a nation of seventy and not seven millions.”

To right the ship of state, Nixon’s challenge was the arduous task of returning the sovereign power of decision to the executive. Faceless bureaucrats and an ascendant Mediacracy (to coin a phrase from Kevin Phillips) turned the duly elected executive into a “sovereign at bay.”

“He is unable to control even his own branch of government, composed of unelected permanent administrators hostile to Republican chief executives and with the media as their ally in any attempt to embarrass or upstage the person in the Oval Office… Eight years of the “Reagan Revolution” did not dismantle the welfare state nor did it scale back the federal bureaucracy…”2

In an interrogation conducted by the Senate's Select Committee on Intelligence, Nixon recognised “certain inherently governmental actions which if undertaken by the sovereign in protection of the interest of the nation’s security are lawful but which if undertaken by private persons are not…”3

This quasi-Schmittian understanding of sovereignty may strike some as un-American4. But it does reflect a discrete tendency in Anglo-Saxon political thought, as both Carl Schmitt and Richard Nixon were drawing from a Hobbesian well.

“In fact Nixon, who In the Arena entitles his most lyrically written chapters “Geopolitics” and “Decisions,” revives the distinction made by German political theorists from Hegel to Carl Schmitt between daily politics and “the political” as the historically significant sphere of activity managed by state sovereigns. It seems plain enough that Nixon does not like the cajoling and glad-handling that accompany ordinary politics. With unmistakable disgust, he depicts Lyndon Johnson as House Majority Leader poking and backslapping his targets of persuasion. And though Nixon puts his severest remarks into the mouths of others when he talks of boorish voters, the expressions of distaste are most likely his own. He is also fond of Thomas Hobbes’s gibe, quoted twice in his book, about democracy as ‘the aristocracy of orators.’”5

(It is likely that his vaunted private anti-semitism (which stood in contradistinction to his public Zionism) stemmed from Schmittian political impulses. For Schmitt’s The Leviathan in the State Theory of Thomas Hobbes was his first publication after the Nazi seizure of power…)

Habermas once quipped that Carl Schmitt believed that “all politics is essentially foreign affairs… {entailing} a people welded together in a battle for life and death asserts its uniqueness against both external enemies and internal traitors.”6 Such a barb applies to Nixon also.

It is equally significant to note that under Nixon’s nose through the 1970s, radicals like Carol Hanisch would develop a diametrically opposed conception of the political. Hanisch and her feminist compatriots maintained that “the personal is political,” challenging private, Protestant, bourgeois institutions like the nuclear family, henceforth inviting political interventions into the private sphere.

In Nixon’s unabridged memoirs, he characterised the liberal myth of the “imperial president” as “a straw man created by defensive congressmen and by disillusioned liberals who in the days of FDR and John Kennedy had idolized the ideal of a strong presidency. Now that they had a strong President who was a Republican… they were having second thoughts and prescribing re-establishment of congressional power as the tonic that was needed to revitalize the Republic.”7

Paul Gottfried, a Jewish-American perpetually in dialogue with the German tradition in political theory, likewise viewed the American presidency as “a bureaucracy under Caesar’s banner, with a debauched chief of state cast into a mock imperial role.”8

Readers who remember the legal issues at the heart of the first Trump impeachment should find the rhythms of this attack on a right-wing executive familiar.

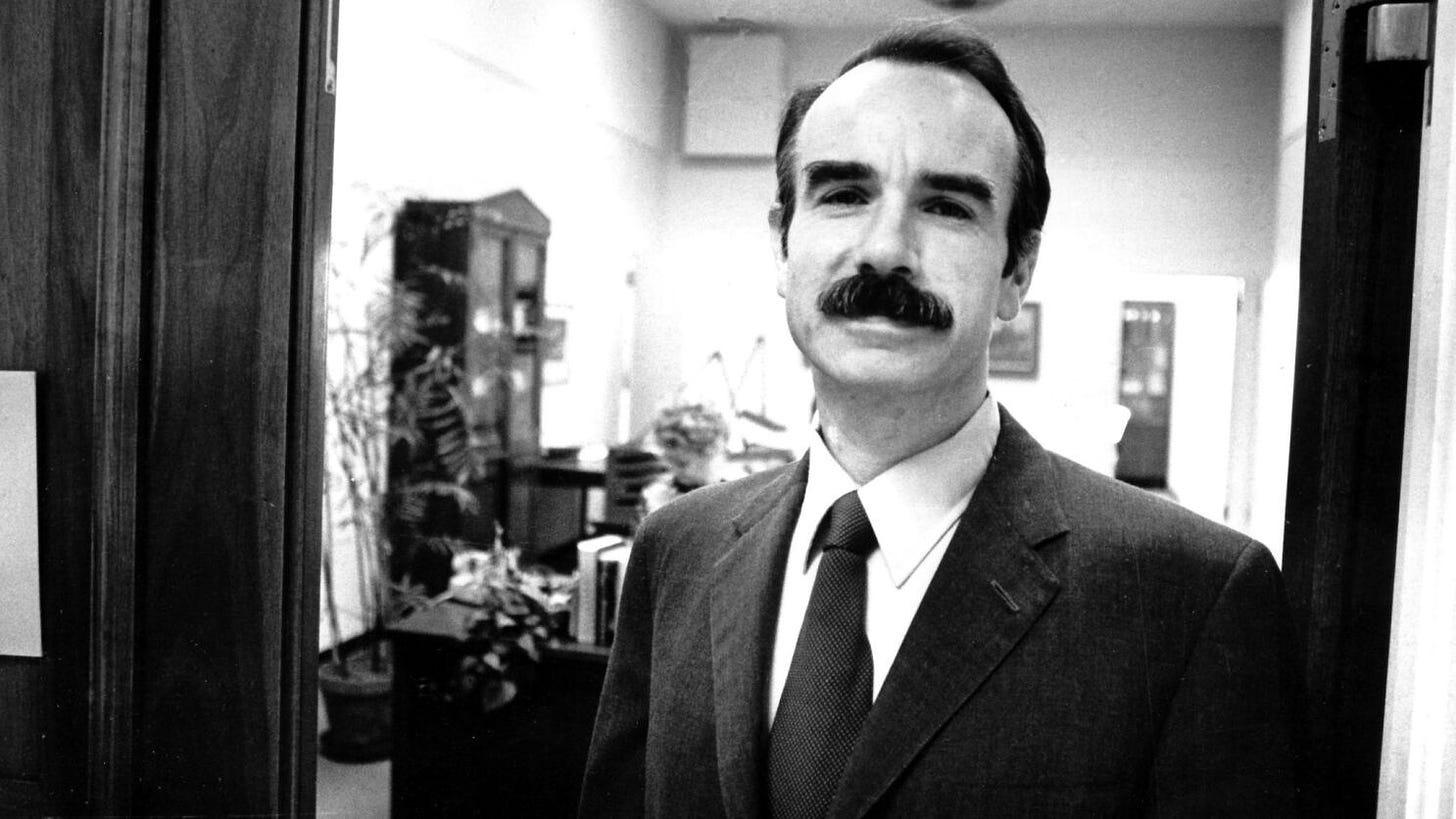

To rectify the president’s preordained powerlessness, top aides Haldeman and Ehrlichman formed the “Berlin Wall,” guarding access to the boss. They would go on to fatally set up a team of Plumbers to keep tabs on subversives like Daniel Ellsburg.

Star pupil G. Gordon Liddy viewed the situation like the total war that it was. In his youth, his Emerson shortwave radio played German music that was “martial and stirring… it made me feel a strength inside I had never known before.” Next came the Horst Wessel, instilling in a young Liddy a belief in a mystical and all-overcoming will as the engine behind the conquest of fear and epochal changes in world history. His teutonic conceptual horizon lingered on in his days as a White House Plumber.

“Our organization had been directed to eliminate subversion of the secrets of the administration, so I created an acronym using the initial letter of those descriptive words. It appealed to me because when I organize, I am inclined to think in German terms and the acronym was also used by a World War II German veterans organization belonged to by some acquaintances of mine, Organisation Der Emerlingen Schutz Staffel Angehorigen: ODESSA.”9

His retrospective portrayal of Hoover’s F.B.I. as an American Schutzstaffel was overstated, as Deep Throat turned out to be Mark Felt, the head of COINTELPRO. The administration was tanked by Watergate, all because Nixon denied this creature of the deep state a promotion upon Hoover’s passing. But true believers like Liddy soldiered on, consoling themselves with German marching songs in prison.

The Bismarckian twist to Nixon’s foreign policy could be viewed as a Germanic trait as well, seeing as a German rapprochement with the Russians has long been recognised as the path to European independence. His shadow government was in large part developed to circumvent the foreign policy establishment. Both factions did battle in the Moorer-Radford Affair, which involved the Joint Chiefs of Staff initiating an espionage operation against the president.

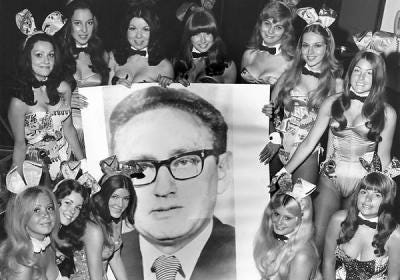

Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, despised by ignorant hippies, was a foreign policy realist with a dash of amor-fati fatalism to spice things up. Like Gottfried, Kissinger was a civilised, bourgeois Central-European Jew, intellectually weaned at the tit of thinkers like Oswald Spengler, and statesmen like Metternich. After the downfall of the house that Nixon built, he would be screwed out of his position of supreme influence by his hillbilly neocon cousins from the Pale of Settlement.10 This is why his present warnings about the quagmire entailed by the establishment's blind support for Ukraine go unheeded.

Georg Iggers characterised historicism as “the main tradition of German historiography and historical thought which has dominated historical writing, the cultural sciences, and political theory in Germany from Wilhelm von Humboldt and Leopold von Ranke until the recent past.”11 Consciously or otherwise, I view Nixon as a participant in this political and intellectual tradition.

We know that in his post-presidency, Nixon called Paul Gottfried’s “The Search for Historical Meaning” the best book he read in 1987. The book concerns the Hegelian roots of postwar American conservatism, and mediates on the American right’s lack of a historical consciousness.

“That same volume is prominently displayed in the Richard Nixon Library in Yorba Linda on the former president's office desk, just as it appeared on the day of his death.”12

In its faith in the executive, foreign-policy coups and some unfortunately technocratic and machiavellian impulses when it came to issues like integration-busing, Nixon’s admin was a purely Prussian creature. Perhaps to save America, one must indulge in some “anti-American” politicking. This means moderation abroad and executive sovereignty at home.

Rest easy, Dick. Rightists of the future would do well to view the world through your jaundiced eyes.

“The Strong Man,” James Rosen

Paul Gottfried’s review of Nixon’s “In the Arena”

“The Odyssey of the American Right,” Michael W. Miles

Though it is quintessentially Hamiltonian, but that’s a story for another article :)

Paul Gottfried’s review of Nixon’s “In the Arena”

“The New Conservatism,” Jürgen Habermas

Nixon’s memoirs

“War and Democracy,” Paul Gottfried

“Will,” G. Gordon Liddy

See “The Forty Years War” by Len Colodny and Tom Shachtman

“The German Conception of History,” Georg Iggers

“Encounters: My Life with Nixon, Marcuse and Other Friends and Teachers,” Paul Gottfried

Nixon will be remembered for opening the way for Red China to become a superpower.