Way Down in the Hole:

"A spirit of national masochism prevails, encouraged by an effete corps of impudent snobs who characterize themselves as intellectuals."

“This is the United States of America

And you've got a right to hate who you want

So let's start busting heads”

“Race War” by Carnivore, from Retaliation (1987)

(How the destruction of white-ethnic power in Baltimore anticipated, in microcosm, current civilisational struggles.)

A review of Kenneth Durr’s Behind the Backlash: White Working-Class Politics in Baltimore, 1940-1980 (2003)

(Editor’s Note: While I was working on this at 4am, Substack’s awful online save system wiped out 2 hours of the best, most rhythmic polemical work I have ever produced. Now I know how Carlyle felt when J.S. Mill’s servant threw his first copy of The French Revolution into the fire. What you see before you is a diminished version of the initial attempt, corrupted by my failing memory. But I suppose it’s fitting considering the subject matter.)

Crime stats ain't got no owners, only spreaders

Believe it or not, I dig The Wire.

It is the exact, rambling, awards-bait, posthumously fellated, self-indulgent dickcheese kind of HBO show that I adore1. Of course, the most ironic thing about my initial consumption of the program in question is that it helped to humanise America’s good PO-lice to a younger yours truly, right as the BLM culture wars were starting to jump off. So in that sense, the latter-day leftist critics of the show on Twitter are right to complain that it wasn’t polemical enough for the vanguard of American race-activism, come 2022.

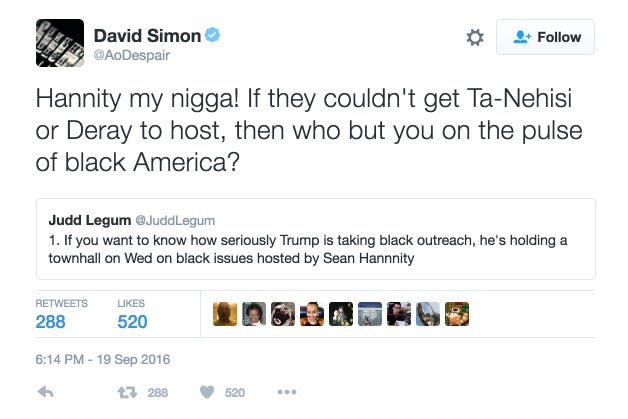

David Simon is an interesting cat. Interesting not for his uniqueness so much as how well he exemplifies a political type. In interviews, I can recall him being very open about the sectarian roots of his political prejudices. He faithfully represents the sensibility of your stereotypical Jewish New Dealer, claiming his intellectually engaged family embodied the old “Three Jews, Five Opinions” trope.

Now of course, when he was a high-schooler in the spring of ‘77, Black Islamist Abdul Khaalis held his father hostage as part of the Hanafi Siege, a sterling exemplar of Black-Jewish relations in the 1970s with the breakdown of their pro-Civil Rights alliance.

"Throughout the siege Khaalis denounced the Jewish judge who had presided at the trial of his family's killers. 'The Jews control the courts and the press,' he repeatedly charged.2"

Simon has been said to have recycled and race-swapped this story for one of his TV shows, a la John Grisham with A Time to Kill but I cannot speak to this claim’s veracity. The point is that, despite his family’s proximity to some memorable incidents of subaltern political violence, Simon’s liberalism remains intact.

His firmly midcentury, moderate worldview leads him to face criticism from all sides.

He has been attacked by retard libertarians who try to appropriate The Wire as some indictment of “muh government,” like the forever-uncharismatic Nick Gillespie of ReasonTV, for daring to raise the social question. He is harangued by teenybopper communists on Twitter for daring to disagree with ACAB — even if this is just a branding dispute — held to account for pushing “copaganda” by not treating Amerikkka’s civil servants like the white devils they are.

Streetwise Conservatives eager to prove they are not the real racists, like Jack Posobiec, have beef with Simon for dropping N-bombs on occasion, as if he was one of the brothers.

And of course, Simon has spent most of his Twitter-time across the last 7 years ranting about the latest indiscretions of those cowardly MAGA Republicans and their dumbfuck hick supporters, voting against their own interests due to their fear of a black planet. One of the greatest screenwriters in TV history was stumped by the Trump, reduced to reproducing the patois of a Tucker Carlson reply guy or the sickeningly bourgeois political anxieties of an MSNBC host fearing for democracy. Another cerebral casualty of the culture war.

I was raised among expatriates, and these people invariably love shows like The Wire — those who have the attention span for TV epics3. Politically, they were anti-totalitarians of a Cold War vintage (in my case hostile to the nation they were doing business in, Red China), proud international liberals, yuppies who nevertheless absorbed a distaste for Reagan/Gingrich Republicans via pop-cultural osmosis.

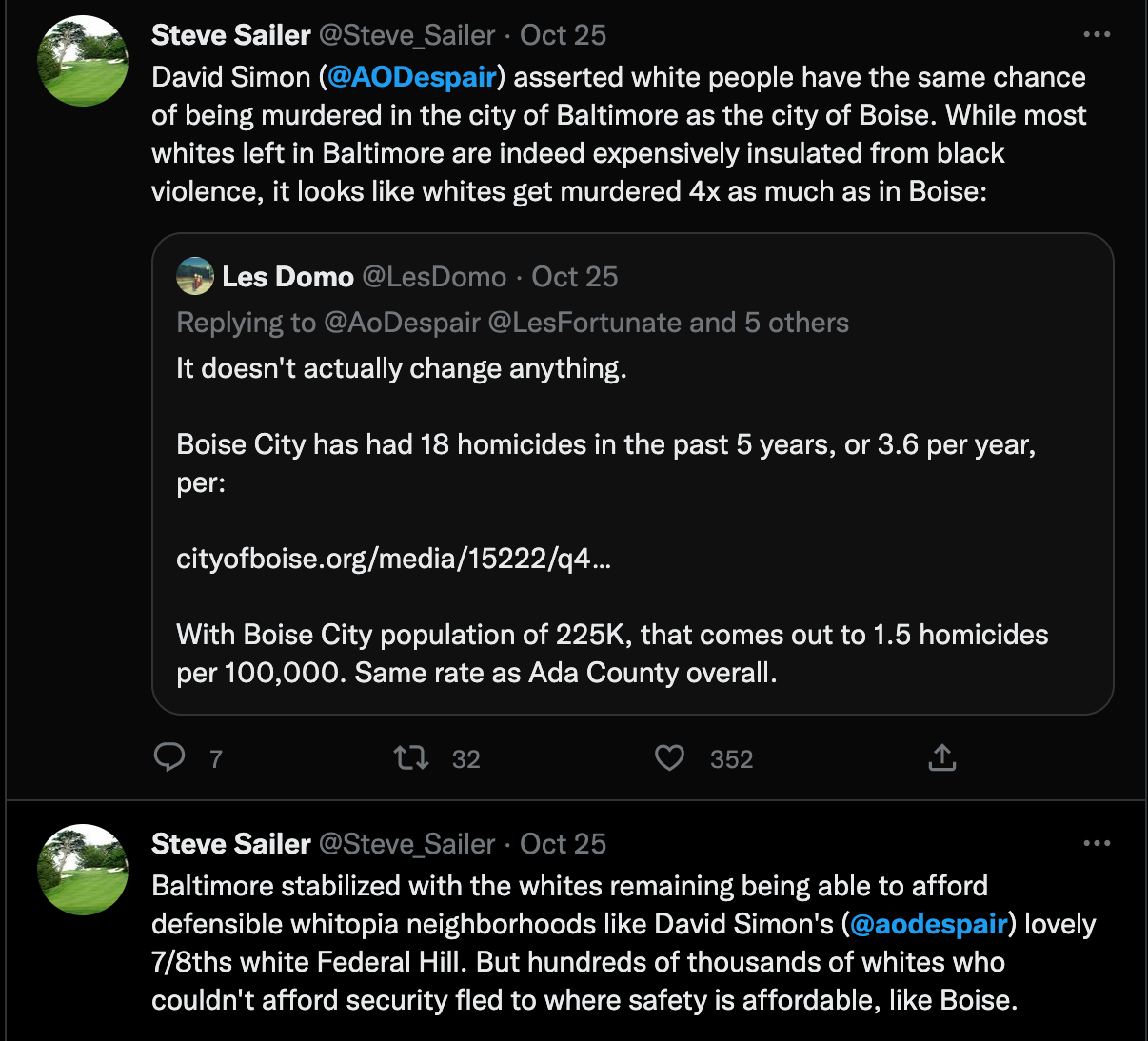

Simon’s internet diatribes have always reminded me of these types, though as a stubbornly American Jew, his liberalism is more rooted in the traditions of a folkway, it is of an earlier make than his cousins’. For his own part, he lives in the “lovely 7/8ths white Federal Hill,” a Baltimore neighbourhood saved from its ‘70s malaise by Baby Boomer gentrification.

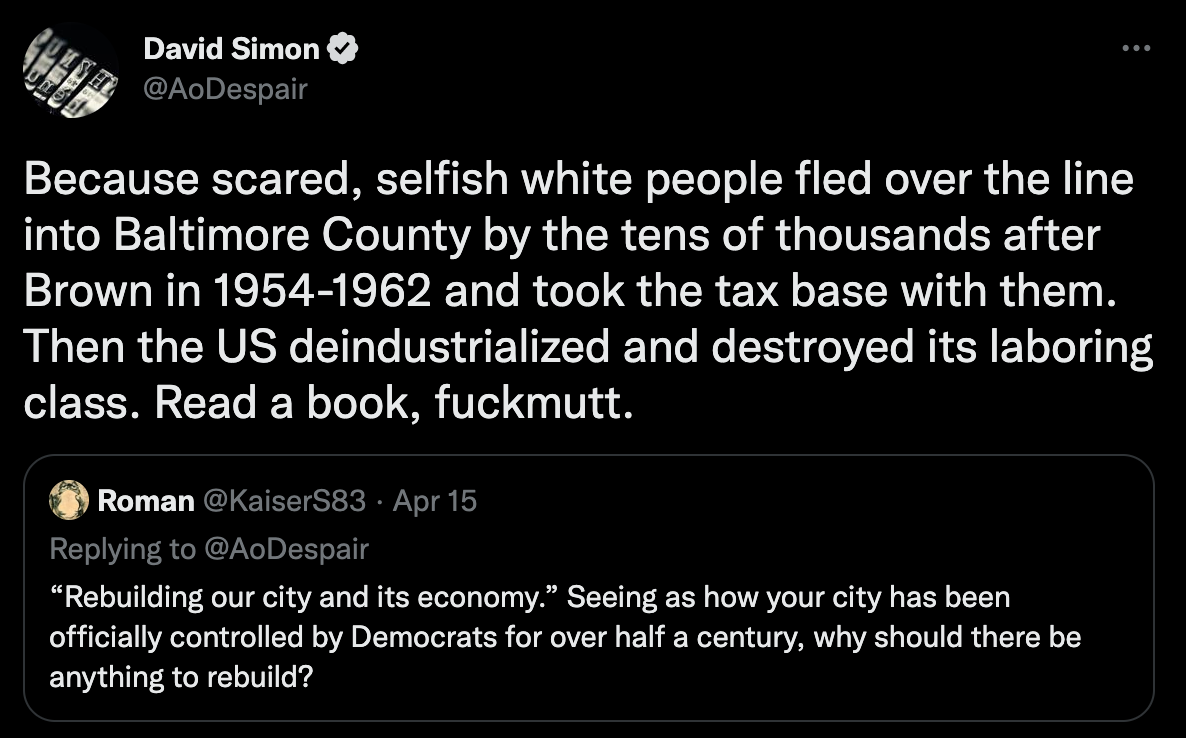

Digressions aside, Simon’s most recent Twitter controversy erupted when he decided to flex on the MAGA chuds with his street cred.

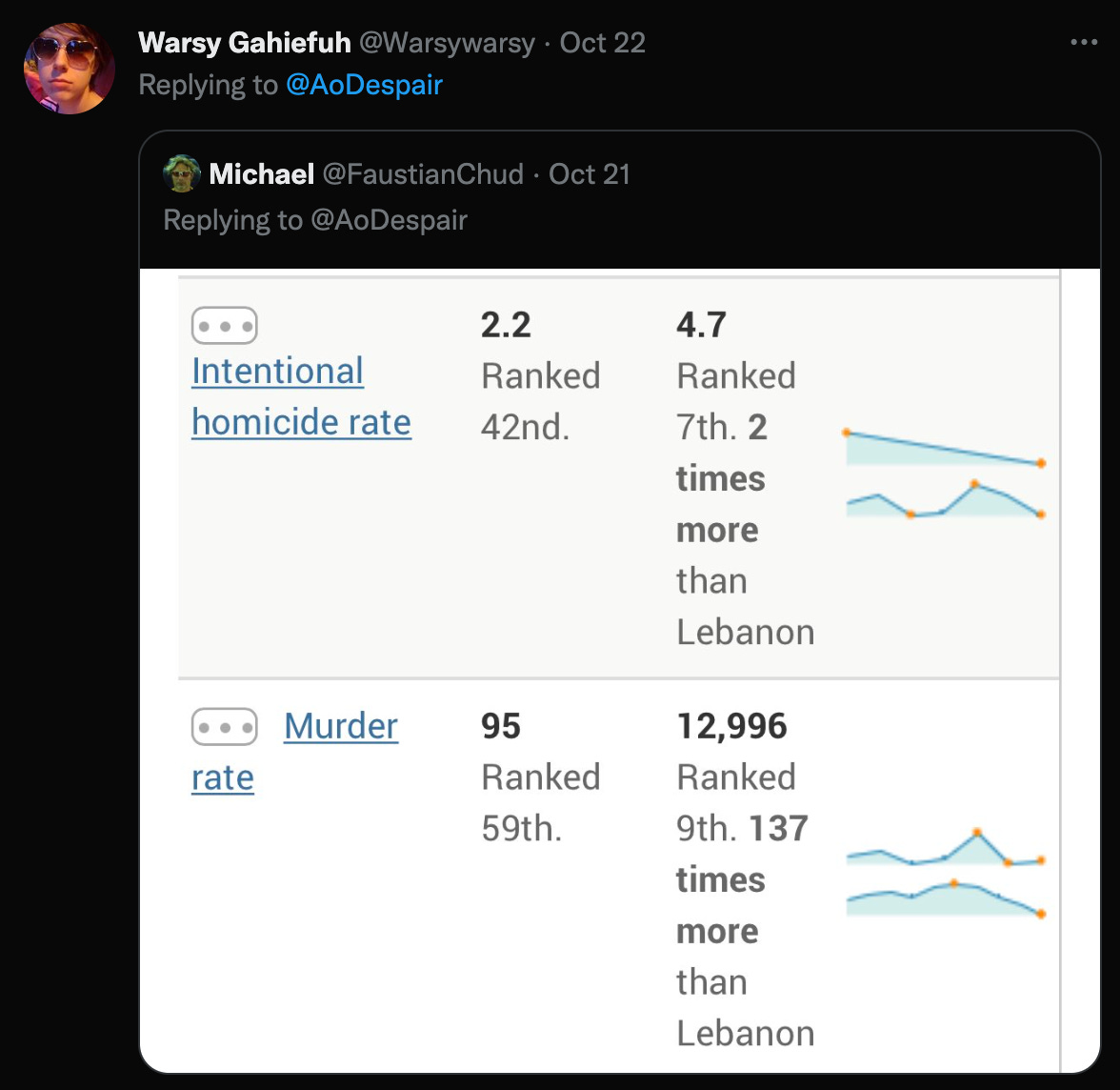

Upon pushback came a segue into beating up on red-states for their relatively high rates of violence. Of course, the amateur criminologists on the dissident right know to attribute this to the large black populations housed in Dixie. Whatever the statistical evidence for this claim, I find it more convincing than the explanation peddled by progressives, which seems to be finger-pointing at those gun-crazy peckerwood hillbillies who vote Republican and fuck their sisters on Sundays.

The ancestrally Democratic denizens of the white working class are very much the fallen angels of the liberal demonology, ripped straight from the frames of Deliverance. They will be very relevant in this piece.

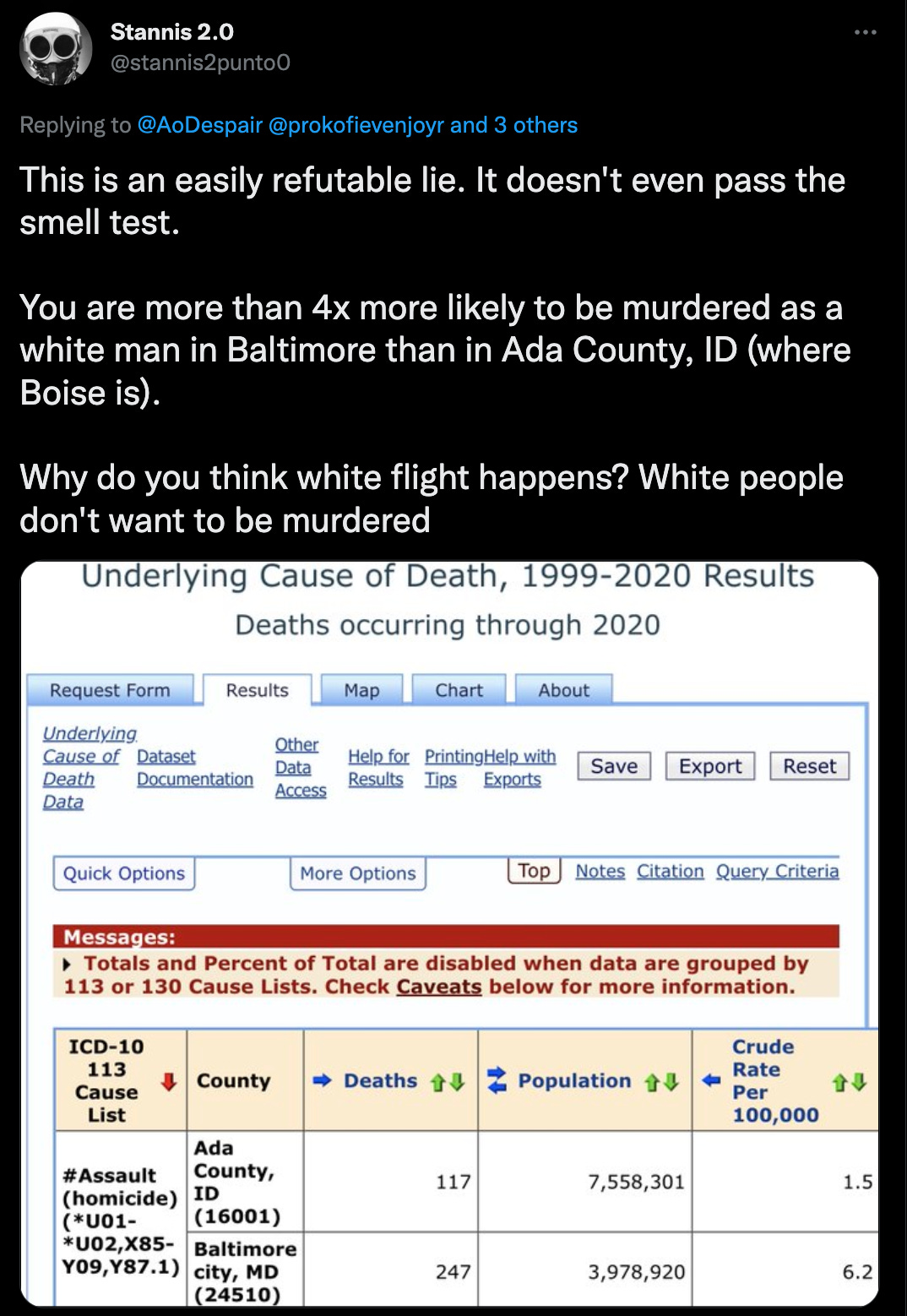

In light of his outlandish attack on Boise, Idaho, a relatively placid place, Frogtwitter descended.

I included a sketch of this Twitter spat to show the dispute over urban criminality that got me thinking about the quality of American decline.

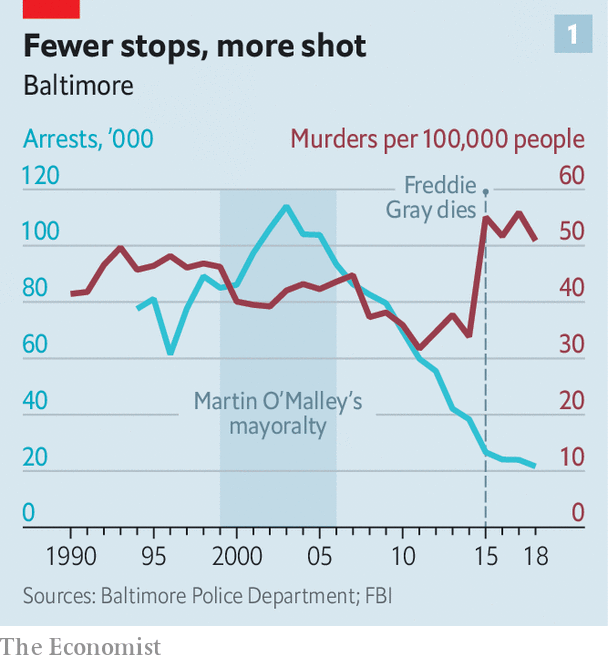

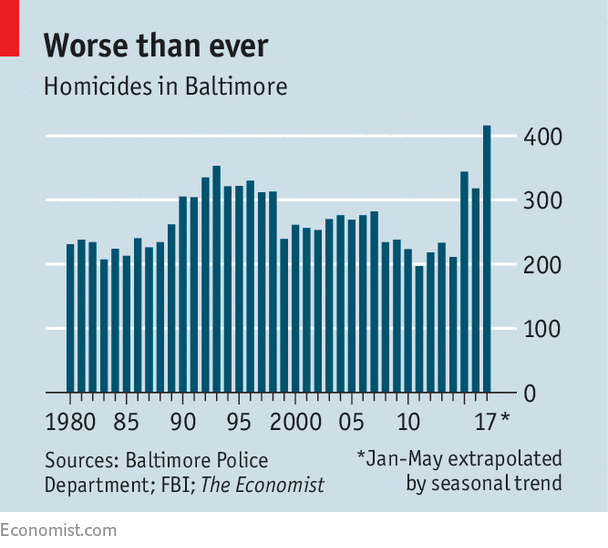

Just how exactly did Maryland go from that genteel Southern state that gave Honest Abe the finger4 to another mid-Atlantic wasteland? Where the state was once known for H.L. Mencken, now its nationally recognised sons are casualties like Freddie Gray.

If you were to ask David Simon for what caused the fall of Baltimore, he raises the typical argument about white flight. Whitey could not stand to live with his melanated countrymen, and crashed the economy with his exit after integration.

But I find this account of white racism as the unmoved mover in American history unconvincing. If anything, it confuses cause and effect. Despite, or maybe because of this frame, Simon’s narrative is actually quite elucidating when it comes to understanding the conventional understanding of the Civil Rights revolution and its consequences.

I’d like to return to one of the professed goals for this blog, for a beat.

To break down the “still largely unexamined birth of the Civil Rights regime and the cultural sentiments it legally incentivised… key to understanding the cultural and political assault on shrinking western majorities that characterises our post-2016 political zeitgeist,” and the cultivation of a “conceptual vocabulary {which articulates} the reality that right-wing men of the west live under {an} occupation, like the subjugated Southerners of the postbellum period.”

“{The} advantage of the Reconstruction frame is that it centres the role of race in political conflicts. The key dilemma of the 21st century, like it or not, will be managing political interactions between different ethno-sectarian groups in an interconnected world. Progressive factions have already issued challenges to old mores based around the doctrine of “diversity, equity and inclusion,” and one must return the serve, preventing the dispossession of those majorities responsible for creating much of the value in modernity.”5

From Sydney to Savannah, Civil Rights history is taught in an insultingly hagiographical way. School kids are spoon-fed linear narratives about Saint MLK redeeming America, putting the nation back on its path to fulfilling contrived “promises of equality.” It is like a history of the French Revolution that stops at the Tennis Court Oath.

There is no exploration of the absurd spike in crime through the Seventies, nor is there much time spent on the escapades of prolific ghetto rioters, nor those forgotten instances of black belligerency through the years, nor bussing, nor the rise of the Civil Rights bureaucracy at the heart of modern wokeness. Explanations for white flight, when offered, are laughably patronising.

When modern pedagogues with an eye towards social policy do dip into the chaotic history to follow, it is highly polemical, coloured by contemporary progressive biases, and what can only be described as an anti-white historiographical methodology. But more on this later.

Historical revisionists must correct this!

Witness the sad state of Civil Rights historiography — where even the Right has bought into 90% of the inherently progressive narrative. By contrast, there have been enough contrarian narratives concerning the causes and conduct of the Civil War to last one a lifetime, thanks to the efforts of Southern antiquarians, even if their views remain unpopular and largely irrelevant.

Revisionism concerning the SECOND Reconstruction is lacking.

The American experience with integration reveals immediate causes behind current crises. It is a period more proximate to our position than the Civil War, a period more important to the narratives driving modern progressivism. It is resultantly more taboo.

Helen Andrews (Boomers) and Chris Caldwell (The Age of Entitlement) have done good work on aspects of the revolution, but there needs to be an EPOCHAL revisionist work on the period in the style of Eric Foner (Reconstruction) or C. Vann Woodward(Origins of the New South) at this point.

I would extend my current demand for Civil-Rights-revisionism to a call for superior histories of the late-Apartheid period as well. One also gets, in high-school, a digression on South Africa’s tumultuous history replete with overlong descriptions of international sports boycotts and more twaddle. Mandela saves the day and rings in the “rainbow nation,” without any mention of the brutal black-on-black “People’s War,” his wife’s fondness for necklacing, or the ANC’s overt ties to the Soviet Union forming an integral component of their strategies of terror.

This is of course, also to say nothing of the post-1994 rash of farm murders, the fate of Zimbabwe and the chaos of S.A. today

The thing to understand about the historical role played by MLK and Mandela is that, though one can quibble over how “red” those two men respectively were, they served the same historical function. Whether their own desires for a state of multiracial equality were sincere or not, calls for non-discrimination functioned as calls for a redistribution of power and wealth, with no end-point in mind.

Sam Francis understood this:

The real meaning of the “doctrine of equality”... cannot be grasped, and its real power as a social and ideological force cannot be countered, merely by a purely formal critique such as that traditionally mounted by the Old Right. The real meaning of the doctrine of equality is that it serves as a political weapon, to be unsheathed whenever it is useful for cutting down barriers, human or institutional, to the power of those groups that wear it on their belts; but, because equality, if nothing else, is a two-edged weapon, it is a sword to be kept well away from the hands of those who merely want to fondle it. It was precisely this understanding of equality as a political weapon that is enshrined in George Orwell’s famous but belated insight in Animal Farm — that all animals are equal, but some are more equal than others.6

The post-60s order did not dismantle old demographic hierarchies so much as it inverted them.

Now back to David Simon, spinning stories about those men among the ruins of Baltimore. Simon blames whitey for Maryland’s misrule. Historian Kenneth Durr takes another tack.

Durr’s Behind the Backlash: White Working-Class Politics in Baltimore typifies the kind of history I enjoy. It is a dense monograph displaying a remarkable degree of sentient empathy for forces reactionary. If one hasn’t noticed, the so-called Silent Majority has been the swing electorate since the Sixties, and has been the subject of renewed attention (read: pathologisation) since the Trump era.

“Many scholars have concluded that the challenge to the New Deal has been due to the politics of race, particularly in the South…

“Kenneth Durr challenges that convention, or at least attempts to complicate that interpretation. As many trade unionists have observed, the Democratic Party of today is not the same organization of a generation ago, much less the one that built the New Deal.”7

Durr blames midcentury liberals for abandoning the interests of increasingly unchic whites. You need only to imbibe in Tom Wolfe’s Radical Chic for a satirical rendering of that impulse.

“One’s heart does cry out—quite spontaneously! — upon hearing how the police have dealt with the Panthers, dragging an epileptic like Lee Berry out of his hospital bed and throwing him into the Tombs. When one thinks of Mitchell and Agnew and Nixon and all of their Captain Beef-heart Maggie & Jiggs New York Athletic Club troglodyte crypto-Horst Wessel Irish Oyster Bar Construction Worker followers, then one understands why poor blacks like the Panthers might feel driven to drastic solutions, and—well, anyway, one truly feels for them. One really does. On the other hand—on the second track in one’s mind, that is—one also has a sincere concern for maintaining a proper East Side lifestyle in New York Society. And this concern is just as sincere as the first, and just as deep…

One rule is that nostalgie de la boue—i.e., the styles of romantic, raw-vital, Low Rent primitives—are good; and middle class, whether black or white, is bad. Therefore, Radical Chic invariably favours radicals who seem primitive, exotic and romantic, such as the grape workers, who are not merely radical and “of the soil,” but also Latin; the Panthers, with their leather pieces, Afros, shades, and shoot-outs; and the Red Indians, who, of course, had always seemed primitive, exotic and romantic. At the outset, at least, all three groups had something else to recommend them, as well: they were headquartered 3,000 miles away from the East Side of Manhattan, in places like Delano (the grape workers), Oakland (the Panthers) and Arizona and New Mexico (the Indians). They weren’t likely to become too much . . . underfoot, as it were. Exotic, Romantic, Far Off . . . as we shall soon see, other favourite creatures of Radical Chic had the same attractive qualities; namely, the ocelots, jaguars, cheetahs and Somali leopards.”8

The abandoned white workers were a comparatively unsexy group riven by contradictions, populist and yet left out in the cold by their New Dealer patrons, who imported a black underclass from the South in order to break their ethnic power base. It was Jouvenel’s high-low versus middle mechanism in action.

“Durr argues that white workers in Baltimore extended political support to the Democratic Party and its New Deal, but only to the extent that it defended their families, neighbourhoods, and workplaces. In time, liberalism would undermine their neighbourhoods, in large part due to desegregation, and white workers would defect.”

“Liberals are not the heroes of this story; they are the elites that wrote editorials for the Baltimore Sun or ran the Democratic Party from the country club. They supported desegregation because they would not suffer any consequences from it (private swimming pools, or those at the country club, were never integrated) and they disparaged those who opposed desegregation.”

“Liberalism abandoned the language and interests of the white working class, particularly when it sought to dismantle segregation which put the schools, neighbourhoods, and homes (and later jobs) of workers at risk. Consequently, liberals relied on the courts more than the electoral process or the editorial page (or television coverage) over letters to the editor, discussions in neighbourhood hangouts, or quickly organized picket lines. In time, white workers would embrace the economic populism and (in retrospect) moderate racism of George Wallace before defecting to Republicans who articulated the defence of "traditional culture and values,” such as Spiro Agnew, Richard Nixon and ultimately Ronald Reagan.”9

Durr is describing the ur-example of “the-left-left-me” politicking in America, albeit vintages of an infinitely more sincere variety than Dave Rubin’s bloviating.

In a way, Behind the Backlash can be seen as a more politically correct and academically respectable version of E. Michael Jones’s The Slaughter of Cities. Kind of like how John Murray Cuddihy’s splendid The Ordeal of Civility was the National-Review-Friendly ancestor of Kevin MacDonald’s Culture of Critique.

Jones recapitulates the story of racial integration in the North from the 1940s on as a form of ethnic cleansing. He sees it as a Jewish-WASP plot to break Catholic power on the coasts, ringing in the New Deal regime by destroying the white ethnic urban neighbourhoods, social institutions that protected discrete ethnic identities and stood in the way of Jewish “moral subversion.”

Durr makes comparably more modest claims, viewing the events in question through a prism of sympathy for the white working class rather than EMJ’s race-blind Catholic paranoia.

But they both agree on the bankruptcy of the liberal program.

The Middle American Radicals, to coin a phrase from Sam Francis, were made politically homeless with the implementation of the Great Society. Though they were “the backbone of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal Democratic coalition,” they would go on to “put Ronald Reagan in the White House.”

Grasping this shift with SYMPATHY and not with condemnation explains American politics today. It is key to forming an understanding of how Lyndon Johnson’s post-landslide legislative springtime transmogrified into liberalism’s Indian Summer.

Spinning out from Durr’s account of the now infamous “Americanization of Dixie/Southernization of America” — “When Southern Politics Came North” — is a portrait of the developing racial consciousness of Northern white-ethnics, soon bound for suburbia.

Durr’s historiographical coup is disarmingly simple to understand. Unlike his liberal colleagues in the historical profession, or cultural opinion-moulders like David Simon, Durr’s shocking innovation is simply taking working-class-whites at their word.

The Moulding of the Neoabolitionist Mind

First, a brief digression into the philosophy of history. It is necessary, before one can grasp the conundrums facing dissident right researchers into either of the Reconstructions.

R.G. Collingwood outlines “the common-sense theory” of historical practice in his essay on “The Historical Imagination.”

“…The essential things in history are memory and authority… History is thus the believing some one else when he says he remembers something. The believer is the historian; the person believed is called his authority.”10

This scheme aligns nicely with one of Friedrich Engels’s political conceits, the claim that revolutions must be authoritarian and total to succeed.

“Have these gentlemen ever seen a revolution? A revolution is certainly the most authoritarian thing there is; it is the act whereby one part of the population imposes its will upon the other part by means of rifles, bayonets and cannon — authoritarian means, if such there be at all; and if the victorious party does not want to have fought in vain, it must maintain this rule by means of the terror which its arms inspire in the reactionists. Would the Paris Commune have lasted a single day if it had not made use of this authority of the armed people against the bourgeois? Should we not, on the contrary, reproach it for not having used it freely enough?”11

In Collingwood’s estimation, the historical process fused the arts and the sciences, due to the historian’s power to discretely select different phylums of evidence in the interest of building narratives.

“There is nothing other than historical thought itself, by appeal to which its conclusions may be verified. The hero of a detective novel is thinking exactly like a historian when, from indications of the most varied kinds, he constructs an imaginary picture of how a crime was committed, and by whom. At first, this is a mere theory, awaiting verification, which must come to it from without. Happily for the detective, the conventions of that literary form dictate that when his construction is complete it shall be neatly pegged down by a confession from the criminal, given in such circumstances that its genuineness is beyond question. The historian is less fortunate.”

“As Descartes might have said… the idea of the past is an ‘innate’ idea.

“Historical thinking is that activity of the imagination by which we endeavour to provide this innate idea with detailed content. And this we do by using the present as evidence for its own past…

“It is for the same reason that in history, as in all serious matters, no achievement is final.”

“This is not an argument for historical scepticism. It is only the discovery of a second dimension of historical thought, the history of history: the discovery that the historian himself, together with the here-and-now which forms the total body of evidence available to him is a part of the process he is studying.”12

It is with a mind for the “history of history,” that one must examine the trends in Reconstruction studies.

Given the eternal law of opportunity cost, the recent trend has been to undermine the authority of white sources while emphasising the authority of BIPOC voices.

The American Conservative’s Helen Andrews sketches the situation well with her controversial piece on W.E.B. Dubois’s now-popular, “neoabolitionist” style of Reconstruction Revisionism:

“If budget numbers are not eloquent enough, we also have the testimony of thousands of Southerners in books, diaries, and letters describing legislators who openly sold their votes for cash and judges who refused to convict thieves who were caught red-handed unless the victim paid the going rate for justice. Du Bois discounts this eyewitness evidence as worthless. “Three-fourths of the testimony against the Negro in Reconstruction is on the unsupported evidence of men who hated and despised Negroes and regarded it as loyalty to blood, patriotism to country, and filial tribute to the fathers to lie, steal or kill in order to discredit these black folk,” he writes.

This is how all Reconstruction revisionists must treat primary sources, as so many lies and delusions. Perhaps there are indeed instances where modern readers might usefully interrogate the motivations behind written testimony. When Southerners write over and over that undisciplined “militias” of armed freedmen made them feel unsafe, drilling in the middle of the street and intimidating local Democrats confident in their immunity from legal consequences, it may be that these fears were partly motivated by racial prejudice. But Du Bois is glib to write off all the evidence this way. In Gaston County, North Carolina, the Union League came to town and, soon after, 28 white farmers had their barns burned down in a single week, leaving the victims destitute and near starvation. Did Gastonians dream that? Did the barns burn themselves?”13

One hopes you can see the political parallel. Sam Francis portrays the historiography’s political coefficient with comparable clarity:

“The meaning of the revolution has long been perfectly clear. The revolution consists of what Lothrop Stoddard, the American racist writer of the 1920s, called in the franker language of that era, "The Rising Tide of Color against White World Supremacy." Regardless of the alarmist connotations that Stoddard's phrase was intended to incite, it ought to be fairly obvious today that the cognitive content of the expression is unexceptionable. You may be for or against "white supremacy" or a "rising tide of color" and you may think either or both of them good, bad, or as morally meaningless as the death of grasshoppers at the end of the summer, but there is not much doubt that not only in the United States in the 70 years or so since Stoddard wrote but also throughout the world, "white supremacy" has been displaced and that the beneficiaries of that racial displacement have been largely non-white or "people of color." This development should not be surprising to anyone who is aware of global demographic trends, let alone to anyone who has paid attention to the fate of the European colonies from the British withdrawal from India to last month's election in South Africa.”14

When it comes to the dismissal of white primary sources, scholars concerned with the Second Reconstruction have also admirably kept up that tradition through the years.

Behind the Backlash

Kenneth Durr takes a different approach. It is truly depressing that a minor monograph out of UNC from 2003 was able to anticipate the killer methodological gimmick at the heart of every political history of America in the last half-decade, at least.

“Having found white working people on the wrong side once too often, historians seem finally to have given up, explaining too much and not enough by invoking ‘‘whiteness’’: the discovery that driving political, social, and cultural change in the postwar workplace and community was white working people’s attempts to protect and expand their unjustly won ‘‘white skin privilege.’’ A corollary to this view holds that the populist arguments put forth by white working people that so startled social observers in 1970 and helped power the Republican resurgence of the 1980s can be best understood as code words for race-based resentments.”15

Yes yes, we’ve all seen the Lee Atwater quote about tax-cutting talk being a substitute for yelling “nigger nigger nigger” like the first users let back onto MuskTwitter. Extrapolation from that comment is flawed, not least of which because liberals are fundamentally ignorant of the concept of containment16. To cut a long thesis short, blind race-hatred was not the only draw of the Reagan-Wallace platforms.

In a review of Robert Self’s “American Babylon,” a study of Oakland’s race relations, Durr generally compliments the work, before chiding Self for his materialistic analysis.

“Perhaps somewhere in his effort to describe the multifaceted and complicated urban-suburban experience Self might have given similar credence to the arguments of white suburbanites. Self does not vilify the working white suburbanite, but he does tend to reduce him to homo economicus. This leads to things like a rather bloodless description of suburbanization as a white attempt to create “residential and industrial property markets”. Well yes, but people thought in terms of affordable homes, safe streets, and good schools, too, and historians might at least consider that they were sincere. Also, despite Self’s Marxian frame of reference (“capital” does a lot of “accumulating” here), the work- place is often discussed but never explored.”17

Historians have, for the most part neglected to consider the perspectives of low-status whites — unsurprising given the political slant of that population.18

“Liberals have tended to see blue collarites as unreasoning opponents; conservatives, as unreflective followers.”19

From the Frankfurt School on, white workers have been seen as nothing but an ungrateful would-be herrenvolk.

“In part because scholars are more comfortable studying those whose convictions they share, working-class and social history is too much the history of the grassroots left. To understand white working-class conservatism historians must approach conservative white working people with empathy and try to understand why they acted as they did.”20

“Monograph writers find much to learn from the postwar struggles of minority workers, but with only a few exceptions they cede the world of the white working class almost entirely to the social sciences. When mentioned at all in new left historical accounts, the white working class too often serves as a foil for the less privileged who still fight the good fight that whites supposedly abandoned after the New Deal.”21

Durr despises this frame of thinking. He seeks to locate a populist continuity in their thinking, to explain their affiliation with people as progressive as Roosevelt and Robert Kennedy, as well as cultural reactionaries like Nixon and Wallace.

Poor whites only ever accepted the New Deal in part. Particularly in the impoverished South, they jumped for joy at its economic benefits, but never fell in line behind the pro-Communist foreign policy of the brain trust in Washington, or its cosmopolitan worldview, one that would slate parochial ethnic identities for extinction.

“During and just after World War II, whites welcomed industrial unionism and wage hikes but opposed shop-floor integration and minority housing projects near their homes. In the fifties, loyalty to neighborhood churches and political clubs grew fierce among workers who did not join the migration to the suburbs.”22

These people fell in line behind George Wallace, big time, particularly in Maryland.

In the 1964 democratic primaries, Wallace overperformed in Wisconsin — a deceptively rural state derisively called “Mississippi North” by liberals upset at its right turn towards figures like Scott Walker and Donald Trump in recent years. With 1/3rd of the vote secured in the Cheese State, he went on to get 30% in Indiana and a whopping 43% in Maryland. Winning the white vote alone (sound familiar, Republicans?), Wallace blamed the “nigger bloc vote” for his defeat.

In 1972 Wallace returned, cleaning McGovern’s clock in Florida, and winning Maryland and Michigan before Arthur Bremer’s bullets put a stop to his comeback. Eventually, his conservative Democrats fell in line behind Richard Nixon in a rejection of George McGovern’s “acid, amnesty and abortion” platform. What came next was the largest electoral landslide since the FDR era.

“Between the eras of Roosevelt and Reagan, in the space of a few short months in 1968, their political sentiments lurched perplexingly between Robert Kennedy and George Wallace.”23

If you understand why that was, you understand the populist current in American history.

“Durr takes to task twentieth-century Democratic liberals for their failure to understand and represent working-class whites. The white working class, he says, very rationally abandoned them.”24

Workers stood behind the Democrats when FDR’s military spending led to “the rapid expansion of Charm City's economic base.”

“Blue-collar Baltimoreans valued the democracy of the New Deal because, among other things, it protected labor unions and provided subsidies for basic industry- policies that white working people believed in. The New Deal consensus, though, left no room for the fact that under the economic and political circumstances of the time, the interests of working whites and working blacks conflicted. In the South a brand of Democratic politics did arise that, for all its highly regrettable draw- backs, took this difference into account. In 1964, a majority of Baltimore’s white working people agreed with Pearl Lowery, a carpenter’s wife who said, “if the State of Maryland does not have anyone who will stand up for the rights of whites as well as colored, then we can support someone who will, even though he is from Alabama.”25

As evidence against the claim that their conservatism was solely rooted in race-hatred, Durr raises the case of Baltimoreans rejecting white economic migrants from the South. Perhaps this is a parallel to the European experience with Polish migrants before the arrival of waves of Middle-Easterners rendered that problem paltry by comparison.

“Migrants from the mountain South were subject to discrimination rooted in a tenacious ‘‘hillbilly’’ stereotype. South Baltimore merchants wanted their money, but most other residents wanted them gone.”26

This would change as the black population of the city grew with suburbanisation.

“Nevertheless, Baltimore natives and white migrant workers found common ground on racial matters. Appalachians, like southerners, had lived under a color line. They shared with other working whites a class consciousness based on whiteness.”27

“There is little evidence that the nature and extent of racism among Baltimore’s white working people changed significantly from 1940 to 1964… Working whites, Mitchell said, rarely looked “for trouble with colored citizens, but they resented even the slightest incursion.” In the postwar years, trouble came looking for them in the form of wartime mobilization, the urban black population explosion, the civil rights movement, the liberalization of the Supreme Court, and federal enforcement of civil rights laws.”28

Their racial concerns were increasingly abstracted as the years went on, as a populist tenor replaced a racialist one. Identification with one’s racial jacket was syncretic with an aversion to the machinations of an alien elite.

“By the early 1960s, the issue of race was joined, but not superseded, by concerns over religious freedom and law and order. Working people saw these problems in populist terms. All appeared to stem from a common source: the misguided exercise of federal power in the hands of a small and unrepresentative elite. Nevertheless, the rhetoric of Baltimore’s 1964 backlash still retained overtly racist elements that were dropped by later practitioners.

“The populist ideas central to the political attack on liberalism that took place in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s entered into working-class conservatism as a part of a southern critique grounded in traditional themes of states’ rights, separate but equal, and white supremacy. Because the hope once offered by populist New Deal rhetoric reverberated in the memories of Baltimore’s working whites, populist arguments were probably the most vital and clearly the most enduring component of the southern argument. But the southern critique was critical because it bore the racial component that New Deal populism lacked.”29

In the eyes of scholars like Durr, the populist streak in the ideas and the rhetoric of white Baltimoreans must be comprehended to make sense of American politics with sympathy.

“Rhetoric aside, however, Durr's point is that between 1940 and 1980, the concerns of urban, white working-class Americans remained consistent, and it was that consistency that led them to support such ideologically disparate leaders as FDR, Joe McCarthy, Robert Kennedy, and George Wallace. FDR's New Deal promised economic security without threatening family, church, and community. McCarthyism promised to guard against communist domination of organized labor. Kennedy opposed a war that many blue-collarites came to see as "illegitimate," and Wallace promised to protect the working class from an increasingly intrusive federal government. Working-class Baltimore's opposition to integration and busing was not simply a racist backlash to the gains of the civil rights movement…

“There was the unfairness of a judicially mandated program for racial equality conceived by suburban middle class liberals but shouldered disproportionately by the white, urban working class. There was the rejection of the rule of law, social responsibility, and the value of work displayed by civil rights activists. And there was the desperate need to preserve those institutions — family, church, and community — that had been central to their way of life for nearly a century.”30

The Nature of the Northern Neighbourhood

“I’m getting to feel like I’d actually enjoy going out and shooting some of these people. I’m just so goddamned mad. They’re trying to destroy everything I’ve worked for—for myself, my wife, and my children.”

Anonymous Ad Salesman to Time Magazine, Sourced from Rick Perlstein’s “Nixonland”

“A passionate tumultuous age will overthrow everything, pull everything down; but a revolutionary age, that is at the same time reflective and passionless, transforms that expression of strength into a feat of dialectics: it leaves everything standing but cunningly empties it of significance.”

Søren Kierkegaard

There is a trope in studies of the Civil Rights era, which raises questions of Southern particularity and the national scope of American "racism." In essence, the cliche is that “Northern whites supported integration for the South until it came to their doorstep.”

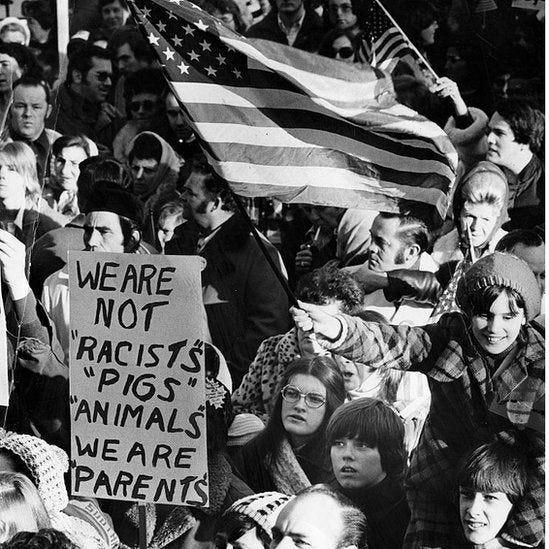

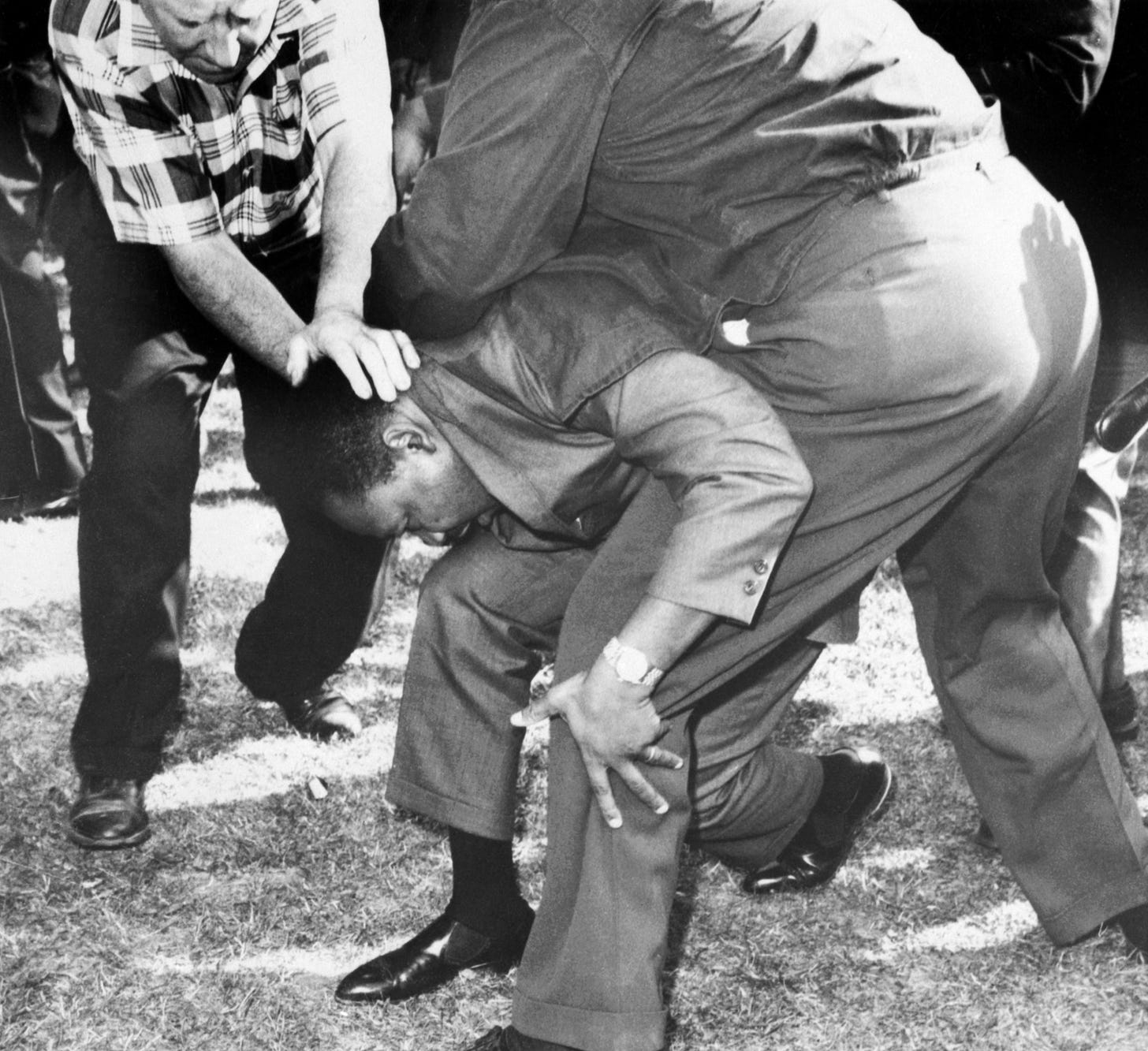

“Most Americans who lived through the civil rights struggle initiated by the Brown decision share a plethora of memories of the era. One of the more enduring visions is that of white residents of the northern cities violently protesting against black "blockbusters" and forced busing. Press accounts represented these people as uneducated, blue-collar, working-class folks. The men were skilled and unskilled factory workers; the women did not work outside the home. Indeed, it was often the women who were at the forefront of the protests. They had watched in horror as Jim Clark's and "Bull" Connor's troopers turned fire hoses and police dogs on civil rights demonstrators. Yet, when the movement "came north," these working-class white men and women, seemingly motivated by the same visceral racial hatred, reacted in much the same manner as had their southern counterparts, albeit without the police and their dogs.31

So why then, was Martin Luther King struck by rocks in Chicago? Why were blacks stabbed with American — not Confederate — flags in Boston over integration busing?

Anti-racist Neoconfederates seeking to preserve what is left of their reputation will raise these incidents to make some puerile points about “them Yankees being the real racists,” and believe me, that reflex will be taken to task in a future piece. 1619 project aficionados also go back to those images when the second phase of their motte-and-bailey attack on American heritage is initiated and an indictment of the nation as a whole is at hand.

There are kernels of truth in both polemical accounts, but to properly understand northern hostility to blacks, one needs to break down sectional differences.

Upon the onset of the 1940s, when government-backed racial transfers, alongside a general great migration out of Dixie, accelerated in earnest, Northern cities had already been blasted with immigration from Europe’s hovels for the last few decades. Ethnic tensions above the Mason-Dixon line were very much along the lines of those identitarian signifiers from the Old Country — petty nationalisms were alive in men’s hearts. Black-and-white distinctions drawn from colonial situations were what you generally found down South, in comparison. This is why, for example, in spite of the ADL’s mythology, incidents like the lynching of Leo Frank stood out in Southern history, for Dixie was not particularly anti-semitic compared to the rest of the West.32 Sephardim honourably numbered among the Confederate dead, while the Ostjuden who flourished in the North, the Ashky ancestors of men like Bill Kristol, became notorious.

The point is to say that the Civil Rights legal regime that was designed to amalgamate a black-and-white South ran into problems when, per the machine logic of mission creep, its scope expanded to the North.

Northern whites were generally moderate liberals in the early stages of the Civil Rights revolution.

“For all their pious sentiments about desegregating the South, whites opposed every single activist step that might have brought desegregation about, and every single activist who was working to do so. In 1961, they thought, by a margin of 57 to 28 percent, that the black students staging sit-ins at North Carolina lunch counters and the “Freedom Riders” occupying segregated buses between Washington, D.C., and New Orleans “hurt” rather than “helped” the cause of civil rights. In 1964, on the eve of the Civil Rights Act, only 16 percent of Americans said that mass demonstrations had helped the cause of racial equality—versus 74 percent who said they had hurt it. Sixty percent even disapproved of the March on Washington, at least in the days leading up to it, while only 23 percent approved.”33

Relations with the South, a junior section kept down by discriminatory freight rates and other tricks, were distant. It was a foreign country to be romanticised in stories like Gone with the Wind, or later demonised in flicks like Mississippi Burning.

“Most Americans, liberal as well as conservative, saw the race problem as something distant. It had to do only, or mainly, with the exotic culture of the South, where segregation was legal. The problem was almost one of foreign policy. The sociologist of race Alan David Freeman wrote of how, sitting in an all-white fifth-grade classroom in New York City in 1954, he had found out about the Brown decision: “I can recall distinctly the response of my own naïvely liberal consciousness . . . The Law is now going to make those bad Southerners behave.”

As white people in the northern and western states saw it, racial harmony had arrived long ago. In August 1962, with the school year about to begin, 83 percent of Americans told Gallup that the blacks in their community had “the same opportunities as white children to get a good education.” Gallup kept asking this question as the 1960s wore on and white Americans’ views changed little. At the end of the 1967–68 school year, 70 percent told pollsters that blacks in their community were treated “the same as whites” and only 20 percent that they were treated not very well or badly.

Outside the South, white people seemed to believe it would be a simple matter to get rid of segregation, as if a system of racial oppression so intricate and ingenious that it had taken three-and-a-half centuries to devise could be dismantled overnight—by sheer open-minded niceness, at no price in rights to anyone. {That} the country could solve a problem of institutional racism without altering any of its institutions.”

What the Yankees would soon realise, was that, as with the 1965 Immigration Act that was rammed through alongside it34, the passage of the Civil Rights Act was lubricated with lies.

“The congressional debate leading up to the Civil Rights Act of 1964 is filled with outright mockery of those who warned of some hitherto unimaginable federal government infringement: not just the regulation of Mrs. Murphy’s rooming house, mentioned above, but also mandatory school busing, public and private hiring quotas, and immigration quotas. In the spring of 1964, when Florida Democratic senator George Smathers worried that attempts to equalize school enrollment might lead to busing, his Pennsylvania Republican colleague Hugh Scott scoffed, “Does the Senator not agree that there is nothing whatever in the bill which relates to the transportation of schoolchildren by bus from one district to another? I find nothing in the bill which pertains to any such provision.” By the 1970s, there was race-based busing nationwide, and not just in Southern states. All sorts of constitutionalist and libertarian fears, chuckled at and pooh-poohed on the floor of the Senate, came to pass. Those who opposed the legislation proved wiser about its consequences than those who sponsored it.”35

At the time of its passage, the North had no idea what it was backing, assuming Civil Rights were a chance to give the Negro a better deal, and to give the South “full membership in the country’s constitutional culture” at last.

Alongside the legal lie came a public relations coup. The few black leaders Northern whites were exposed to were men like MLK, those “integrationists” assailed by Black Nationalists like Harold Cruse.

“Harvard sociologist Nathan Glazer recalled that interracial fraternity “was certainly the objective of the American Negro civil rights movements until the late 1960s—black leaders wanted nothing more than to be Americans, full Americans, with the rights of all Americans.”36

In Durr’s case study, “King's generation of leaders espoused civil rights — "rights that commanded universal respect,”37 which appealed to white ethnics proud of their pluralist society.

This would later change as blacks became more boisterous. Five days after the passage of the Voting Rights Act, Los Angeles was in flames.

“A kid stepped up to the microphone. He was sixteen, but he looked younger.

“I’m going to tell it the way it is,” he began. “I’m gonna tell you somethin’. Tonight there’s gonna be another one, whether you like it or not.”

Murmurs.

He raised his hand for attention, his face intensifying. “Wait! Wait! Listen. We, the Negro people down here, have got completely fed up. And you know what they gonna do tonight. They not gonna fight down here no more. You know where they go in’. They after the white people. They gonna congregate, they gonna caravan out to Inglewood, to Marina Del Rey”— someone tried to push him away from the microphone—“and everywhere else the white man’s gonna stay. They gonna do the white man in tonight!”

There was applause.

The human relations commissioner begged local stations not to air the clip that night. They showed it anyway. Angry whites had begun mobbing sporting-goods stores. More TV images, these ones to scare Negroes: Caucasians siting down the barrels of rifles, stockpiling bows and arrows, slingshots, any weapon they could lay their hands on. Race war seemed imminent. In the integrating community of Pasadena, a little girl lay awake at night wondering whether the new family moving in down the block was going to burn down her house while she slept, she remembered forty years later.

The terror was compounded by administrative chaos within Governor Edmund “Pat” Brown’s Democratic administration. Brown was on vacation in the Mediterranean.

“…Some whites noticed a pattern: in 1964, rioting had broken out a few weeks after the signing of the last civil-rights-law-to-end-all-civil-rights-laws. Watts wasn’t even the only riot that week; in Chicago, a black neighborhood went up after an errant fire truck killed a woman. Some whites noticed some liberal politicians seemed to be excusing it all. Time quoted Senator Robert F. Kennedy: “There is no point in telling Negroes to obey the law. To many Negroes the law is the enemy.”

But what were we left with without respect for the law? Time answered that question by quoting a “husky youth”: “If we don’t get things changed here, we’re gonna do it again. We know the cops are scared, and now all of us have guns. Last time we weren’t out to kill whites. Next time is going to be different.”

Lyndon Johnson, petrified, instructed federal agencies to pump $29 million into the neighborhood—in secret, for fear of charges he was pandering to rioters, for fear that rising expectations would lead but to more chaos (“Negroes will end up pissing in the aisles of the Senate”). The Republican Policy Committee, meeting at the end of August, took a side on Watts— Chief Parker’s, who argued that the civil rights movement was responsible for the violence. Congressmen’s mail changed overnight: “People are saying that the Irish had their problems and the Italians had their problems, but that they didn’t turn to civil disobedience,” a West Pennsylvania Democrat told the president. Los Angeles’ Democratic mayor, Sam Yorty, a Nixon supporter in 1960, began boasting of never having visited Watts and received a standing ovation from a businessmen’s luncheon when he said of the white Sacramento guardsmen sent down to his city, “What a difference between these fine young men and the people they were sent to control!”38

“As black militants adopted the rhetoric of black rights,” conservative whites switched from defending the rights of whites to “working people” more broadly. The racial struggle was inverted.

“In 1954 protesting parents were condemned by nearly all community leaders, who could easily discount their arguments on the grounds of racism. By the early 1970s, though, racial language had been effectively removed from white working-class protests. Even though the issue of busing ultimately revolved around race, opponents effectively argued that the real problems were class bias and the insensitivity of bureaucrats… With the 'racist' label removed, white working-class arguments gained new legitimacy.”39

Looking back on the constitutionally tumultuous decade, Christopher Caldwell cites the legal scholar Herbert Wechsler40 for his insight that the Brown decision fundamentally gutted the “freedom of association” right that was at the heart of American pluralism.

“Brown granted the government the authority to put certain public bodies under surveillance for racism. Since the damage it aimed to mend consisted of “intangible considerations,” there was no obvious limit to this surveillance. And once the Civil Rights Act introduced into the private sector this assumption that all separation was prima facie evidence of inequality, desegregation implied a revocation of the old freedom of association altogether.”41

Liberal scholars treated Southern appeals to “freedom of association” as nothing but dogwhistles, and the legal argument has since been abandoned by all but oddball libertarians like Rand Paul. Nevertheless, intellectuals at the time understood the Brown decision’s profound cultural import. Caldwell raises Leo Strauss’s objections, presumably to make his logic easier to stomach for Lincolnian Claremonsters.

“A liberal society stands or falls by the distinction between the political (or the state) and society, or by the distinction between the public and the private. In the liberal society there is necessarily a private sphere with which the state’s legislation must not interfere. . . . liberal society necessarily makes possible, permits, and even fosters what is called by many people “discrimination.”

“The prohibition against every ‘discrimination’ would mean the abolition of the private sphere, the denial of the difference between the state and society, in a word, the destruction of liberal society.”42

Monarchists rejoice, for the so-called “liberals” of America have, through their racial guilt, returned us to the medieval, volkisch order outlined by the conceptual historian Otto Brunner in his Land und Herrschaft.

The quotes from Strauss are sourced from a lecture of his on “Why We Remain Jews.” In context, the remarks are an even more damning indictment of the managerial apparatus the Civil Rights push strengthened, comparing it, as Burnham did, to the Soviet system.

“Now, we have empirical data about this fact, the abolition of a liberal society and how it effects the fate of Jews. The experiment has been made on a large scale in a famous country, a very large country, unfortunately a very powerful country, called Russia. We all are familiar with the fact that the policy of communism is the policy of the communist government, and not of private, fraternitylike or other, organizations, and this policy is anti Jewish. That is undoubtedly the fact.

…It is impossible not to remain a Jew. It is impossible to run away from one’s origins. It is impossible to get rid of one’s past by wishing it away. There is nothing better than the uneasy solution offered by liberal society, which means legal equality plus private “discrimination.”43

Caldwell follows his logic to its conclusion.

“By the time Glazer wrote, he could see what Wechsler had predicted: Giving blacks access to “the rights of all Americans” would mean redefining those rights, starting with freedom of association.”44

The destruction of a night-watchman state that protected pluralism, even before Affirmative Action45 was ordered to ensure racial representation, posed a fundamental threat to the fractious ethnic structure of the North. Legal tools jury-rigged for places like Georgia and Mississippi proved to be blunt instruments when applied to über-segregated cities like Chicago, a town more comparable to Belfast than Birmingham.

“The proudest achievement of the American model of ethnic assimilation was its pluralism. Even if suburban parts of the country appeared to be growing blander and more homogeneous, they had issued out of, and still co-existed with, a thrilling and varied culture of mostly European inheritance: Jewish yeshivas, Chinese restaurants, Italian Catholic folk festivals, Slovak veterans’ lodges, Irish musical groups, Polish trade unions, and even Anglo-Saxon yacht clubs. Civil rights legislation put not just Jim Crow but all of American culture up for re- examination and renegotiation. “For one of the major groups in American life,” Glazer wrote of black people, the idea of pluralism, which has supported the various developments of other groups, has become a mockery. Whatever concrete definition we give to pluralism, it means a limitation of government power, a relatively free hand for private and voluntary organizations to develop their own patterns of worship, education, social life, residential concentration, and even distinctive economic activity. All of these enhance the life of some groups; from the perspective of the American Negro they are exclusive and discriminatory.”46

The neighbourhoods built to protect specific ethnicities, and not a race, were under attack.

To understand the ferocity with which white-ethnics defended their turf, one must examine the role of the neighbourhood that the anti-pluralist integration regime threatened.

“These were places where people lived for generations, often in the shadows of the factories that gave employment to successive generations of neighborhood boys. The residents' sense of commitment to family, church, and community was extraordinarily strong and informed by "the Roman Catholic principle of subsidiarity. . . [, which] held that society was best understood as a hierarchy extending from church and state at the top to neighborhood and family at the bottom, and what is most significant, [held that] no higher level entity was expected to undertake a responsibility properly belonging to a lower-level association”47

Subcommunities, as Glazer called them, were often suspicious, hostile to outsiders. They were also indispensable for giving people of humble prospects a dignified place in the social order, and keeping the ruthless machinery of market competition at bay. “The force of present-day Negro demands,” Glazer wrote, “is that the subcommunity, because it either protects privileges or creates inequality, has no right to exist.” Now government would set about destroying those subcommunities—eventually doing so in the name of “diversity.”48

Why, it sounds like an integralist’s dream, if only a bit more racist.

“It was the responsibility of the federal government to insure the continued well-being of family and community. This the New Deal did, promising "social security rather than social change." Thus it was supported by Baltimore's white working class.”49

Beyond the somewhat deceptive portrayals of a socially conservative New Deal, it is true that FDR’s parlour tricks provided white immigrants, üntermenschen in the eyes of that era’s “economically royalist” Republican Party, with a degree of security. It is why, in the closing weeks of the 2022 midterms when I am writing, modern Democrats, having failed to attract votes with shrill appeals to lost post-1960s abortion rights, have resorted to circling the wagons on the threat of a recalcitrant GOP congress delivering entitlement cuts.

Christopher Lasch, a leftist-turned-traditionalist50, inveterate enemy of elites, and scholar of the breakdown in American social life would glowingly describe the social role of the neighbourhood in his Revolt of the Elites. They were a political bulwark close enough to the people to provide them with tangible benefits, while representing forces powerful enough to get concessions from governments, to swing elections.

Lasch’s chapter on “Racial Politics in New York: The Attack on Common Standards” calls out those “policies intended to break up ethnic neighborhoods that allegedly stand in the way of racial integration.”

To Lasch the neighbourhoods were “strong, cohesive — but exclusionary,” enduring “based on ethnic and familial ties and highly parochial as a result.” The old ethnic neighbourhood would “provide shelter from the anonymity of the market, but they {would} also prepare young people for participation in a civic culture that reaches far beyond the neighborhood.”

These great American cities would, of course, be ravaged by the speculation economy and the financialization of America. As the Cold War system wound down, cities lost their function as worker barracks.51 In a chicken-or-the-egg conundrum, cities or states where family formation was unaffordable elected Democrats as a rule52. As seen in New York and California today, Democrat policies drive out the Middle Class53. A middle class that functions as the electoral base for the post-Nixon GOP, a petit-bourgeoise that functions as the social base for nationalist movements in history, and the cultural class least bullish on "wokeness."

“The urban economy continues to deteriorate. The flight of industry creates a vacuum that is only partially filled by finance, communications, tourism, and entertainment. The new industries do not provide jobs for the unemployed. New York needs a tax base and full employment; instead it gets words and symbols and lots of restaurants. The new industries encourage a self-absorbed, hedonistic way of life, one deeply at odds with the way of life promoted by family-centered neighborhoods. Real estate speculation—an industry, as Sleeper points out, that “is to New York City what big oil has been to Houston”—is equally subversive of an older way of life, since neighborhood turnover is more profitable than neighborhood stability. Speculators let buildings run down and then collect insurance when they go up in flames. The real estate industry spreads the word that a given neighborhood is on the rise or going down, thus “creating self-fulfilling prophecies of neighborhood improvement or decay.”

“The business and professional classes, for the most part, make up a restless, transient population that has a home—if it can be said to have a home at all—in national and international organizations based on esoteric expertise and dominated by the ethic of competitive achievement. From the professional and managerial point of view, neighborhoods are places in which the unenterprising are left behind—backwaters of failure and cultural stagnation.”54

Under the Soviet system, the assault on discrete national identities within the former Russian Empire was affected by a system of internal deportations, implemented postwar as a retaliatory gesture towards groups accused of collaborating with the Nazis.

In a post-New-Deal, post-Great-Society America, the breakup of the (ethnic) neighbourhoods was justified by what else but the regime’s supreme mantra: a demand for “diversity, equity and inclusion.”

“Political battles over open housing and school desegregation have exposed neighborhoods to additional criticism on the grounds that they breed racial exclusiveness and intolerance. From the mid-sixties on, the racial policies favored by liberals have sought to break up the black ghetto, another kind of undesirable neighborhood, at the expense of other ethnic “enclaves” that allegedly perpetuate racial prejudice. The goal of liberal policy, in effect, is to remake the city in the image of the affluent, mobile elites that see it as a place merely to work and play, not as a place to put down roots, to raise children, to live and die.”55

The focus of a top-down, individual-rights-based liberalism, and the elitist tastes of the social planners who implemented such schemes, killed off any hope for a popular black nationalism.

“Racial integration might have been conceived as a policy designed to give everyone equal access to a common civic culture. Instead it has come to be conceived largely as a strategy for assuring educational mobility. Integrated schools, as the Supreme Court explained in the Brown decision, would overcome the psychological damage inflicted by segregation and make it possible for black people to compete for careers open to talent. The misplaced emphasis on professional careers, as opposed to jobs and participation in a common culture, helps to explain the curious coexistence, in the postsixties politics of race, of a virulent form of cultural particularism (according to which, for example, black children should read only black writers and thus escape exposure to “cultural imperialism”) with strategies having the practical effect of undermining particularism in its concrete expression in neighborhoods.”

This “cultural particularism” is today called “wokeness.” Its devotees do not seek political separation from whites, as, say, Irish Nationalists seek separation from Ulster, but do plan to leech off of them.

The representatives of this new breed of black activism are no longer the straight-laced (at least on the surface), socially conservative preachers of MLK’s day, who appealed to Natural Law and Christian ethics, but are often upwardly-mobile immigrants taking advantage of America’s ambiguous race-consciousness. The Kenyan-American Barack Obama, the Indian-Jamaican Kamala Harris, the Nigerian-American Ayọ Tometi… Most amusingly, Democratic Senator Cory Booker, born to pioneering black IBM executives, grew up in Harrington Park, a New Jersey suburb now 80% White, 13% Korean and 0.69% Black.

Harold Cruse, in his Crisis of the Negro Intellectual thought assimilation would end black culture — and so far the caste raised up from the underclass by affirmative action and integration has been poached by and assimilated into liberalism, and the global subaltern attack on the white world.

We must now turn back to Lasch’s account of the white neighbourhoods, who tenuously welcomed integration at first.

“Liberals took for granted a “social order cohesive and self-confident enough to admit blacks” on its own terms. There was a great deal of racial tension and injustice, but there was also a considerable reservoir of goodwill on both sides. White ethnics, Sleeper thinks, were still “up for grabs.” Uneasy about black migration into their neighborhoods, they were nevertheless committed to principles of fair play…

“Those who feared or resented black people found themselves disarmed by the moral heroism, self-discipline, and patriotism of the civil rights movement. Participants in the movement, by their willingness to go to jail when they broke the law, proved the depth of their loyalty to the country whose racial etiquette they refused to accept. The movement validated black people’s claim to be better Americans than those who defended segregation as the American way. By demanding that the nation live up to its promise, they appealed to a common standard of justice and to a basic sense of decency that transcended racial lines.”56

This is the side of the story we are all familiar with. The glorious triumph of the revolution, before it devolved into its current excesses. Next came the redefinition of equality57 and the construction of a new caste system extolling the virtues of the put-upon noble savage, the moral superiority of the subaltern.

“The social engineering initiated in the mid-sixties, on the other hand, led to a rapid deterioration of race relations. Busing, affirmative action, and open housing threatened the ethnic solidarity of neighborhoods and drove lower-middle-class whites into opposition… Black militants encouraged racial polarization and demanded a new politics of “collective grievance and entitlement.” They insisted that black people, as victims of “white racism,” could not be held to the same educational or civic standards as whites. Such standards were themselves racist, having no other purpose than to keep blacks in their place. The white left, which romanticized Afro-American culture as an expressive, sexually liberated way of life free of bourgeois inhibitions, collaborated in this attack on common standards. The civil rights movement originated as an attack on the injustice of double standards; now the idea of a single standard was itself attacked as the crowning example of “institutional racism.”58

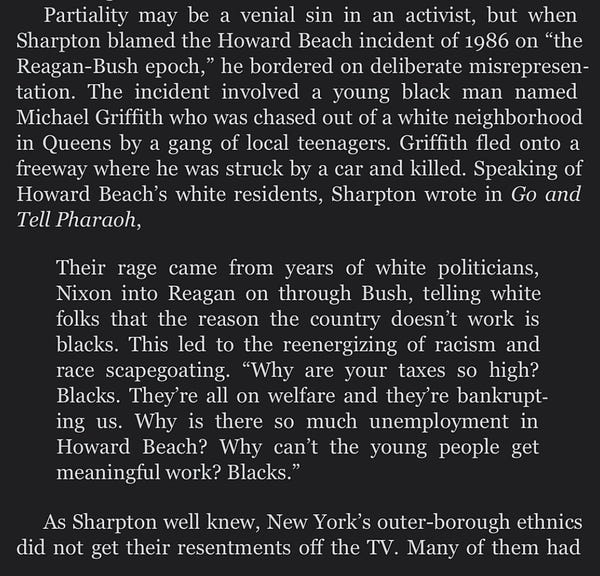

Then came the construction of the Civil Rights racket, a system of moral blackmail designed to extract concessions from majorities and for elite vanguards championing minority interests. Lasch raises the famous Tawana Brawley hoax pushed by professional negros like Al Sharpton as an example of the retreat from truth in favour of tropes, on the part of black militants.

“Anthropologist Stanley Diamond argued in the Nation that “it doesn’t matter whether the crime occurred or not.” Even if the incident was staged by “black actors,” it was staged with “skill and controlled hysteria” and described what “actually happens to too many black women.” William Kunstler took the same predictable line: “It makes no difference anymore whether the attack on Tawana really happened. ... [It] doesn’t disguise the fact that a lot of young black women are treated the way she said she was treated.” It was to the credit of black militants, Kunstler added, that they “now have an issue with which they can grab the headlines and launch a vigorous attack on the criminal justice system.”

See also Duke Lacrosse, see also Bubba Wallace, see also the saga of Jussie Smollett. Those all-too common defences the hate hoaxes remind one of what Julius Evola said in defence of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion — that they were factually false but spiritually true.

And although black norms seem dominant in American culture now, a component of Harold Cruse’s critique did come true. African-American elites, and elites alone, have profited from their assimilation into the Bioleninist ruling caste.

“It is (or ought to be) a sobering experience to contemplate the effects of a campaign against “racism” that turns increasingly on attempts to manipulate the media—politics as racial theater. While Sharpton and Maddox “grab the headlines,” living conditions for most of the black people in New York continue to decline.”

“Affirmative action gives black elites access to the municipal bureaucracy and the media but leaves the masses worse off than ever.”

Not only does the Civil Rights regime undermine the classically liberal meritocracy, challenging the point of the American project as liberalism turns to racial redistributionism, but “most blacks do not advance at all and… they are held back by the very militance that is supposed to set them free.”

To Lasch, they are paternalised by victimization — this is a basic conservative point. – “And thereby perpetuate one of the deepest sources of failure: the victim’s difficulty in gaining self-respect.”

Lasch claims that “young people in the black ghetto” turn violent at the thought of an “affront to one’s honor – ‘dissing’” that justifies a violent retaliation. The popularity of Malcom X via Spike Lee “can be understood as a politicized version of this misplaced preoccupation with violence, intimidation, and self-respect.” Supposedly MLK is now condemned as an Uncle Tom concerned with placating whites rather than resisting them.

“His insistence that the civil rights movement needed precisely to allay white fears, not to intensify them, has become utterly incomprehensible—for eminently comprehensible reasons—to those who can no longer distinguish between fear and respect.”

This is where Lasch’s neo-populist argumentation falls apart for me.

Personally, I don’t see how one can view MLK’s crusade into the ethnic neighbourhoods of Chicago as something other than a manifestation of the same machinations designed to smash ethnic political power with the tools of racial levelling developed in, but not exclusively for, the South.

The canard I began this section with was half-true. Rich northern liberal whites largely escaped the process of integration, while poor whites had to bear the brunt, and were radicalised in the process59.

A Populist Style

“The rise of anticommunism in the postwar years spurred the construction of a new populist class politics. In the 1930s blue-collar Americans had targeted elite opponents in corporate boardrooms—‘‘economic royalists,’’ as Roosevelt called them—but by the 1950s they viewed the denizens of universities and bureaucracies—policymakers rather than moneymakers— as the bigger threat to working-class life. This new populism was fundamentally conservative; its adherents could champion existing American institu- tions while castigating key officials.”

Kenneth D. Durr, “Behind the Backlash”

Durr’s text should land with modern Right-Wing populists, for showing how their ancestors’ concerns were sincere, and their politics were more consistently anti-liberal than they were anti-black.

“Underneath major shifts lie continuity, according to Kenneth D. Durr. White workers' chief concerns were always their neighborhoods and institutions. The changing objects of their scorn — economic royalists in the Roosevelt years and liberal university and government bureaucrats by the seventies — reflected an ever-present disdain for elites. Of course they were racially antagonistic, Durr says, but their rhetoric on workers' rights, citizen responsibilities, and community control are to be regarded seriously.”60

This is Durr’s view of the white ethnics, a voter base as repulsed by forced integration as they were by the Vietnam War. It was a populist love for the in-group, and not a hatred for any out-group that drove their actions.

They evinced a hatred of silk-stocking Republicans, and that ascendant cadre of effete, elitist liberal Democrats. They grew estranged from late stage New Dealers like David Simon, who betrayed low-status whites with their out-group sympathies. These natural populists, swaying from Red to Brown, bolted from the party.

Lasch agrees with this assertion:

“{New York} City’s beleaguered white ethnics know that ... it isn’t really minorities they’re losing out to; there are the eternal rich and a new managerial elite that, in an exquisite irony, includes radicals who tormented them in the sixties and then cleaned themselves up in the eighties to claim their class prerogatives.”61

The white ethnics, ready-made with a soft spot for fighting Irish Rightists like Joe McCarthy, already hailed from a starkly different culture to that of the architects of the New Deal.

“White Baltimore workers were a conservative group who applauded anticommunists, professed a populist anti-elitism, devoted themselves to their churches, and expressed fierce loyalty to their neighborhoods."

“By the 1960s however, Baltimore’s white workers perceived themselves to be under siege, particularly from the prospect of residential desegregation. Willing to accept the integration of many public spaces, they drew the line at housing and schools, protesting vigorously and sometimes violently at what they viewed as black encroachment on their rights. For Durr, more was involved than “sheer race hatred,” even though there was plenty of “unabashed racism” to go around. “The threat to their neighborhoods was real”; blockbusting and lower property values posed genuine risks to their substantial investments in their homes. The decline of manufacturing jobs and plans for redevelopment —- including the building of freeways through their neighborhoods — further undermined their formerly secure worlds.”62

The indelicate force of the invisible hand, driving ethnic migration within the Union, irreparably destabilised the institution of the ethnic neighbourhood.

“Whites blamed various elites — liberal politicians, judges and journalists — for failing to address rising crime rates and cultural deterioration and for making white workers disproportionately bear integration’s costs. Race was part of the equation, Durr admits, but white workers’ demands for law and order also encapsulated “fears about the decline of their neighborhoods.” The rise of a “rights-based liberalism63 that could no longer protect, or even sanction, the institutions and ideals of the urban white working class” in the 1960s fatally undermined the older New Deal liberalism.”64

The desegregation process exposed divisions between white elites and the proles who had to suffer the consequences of their ideological initiatives.

“When desegregation came in the 1970s, it cost employers little but white workers paid a great cost (or at least had their sense of security upset), and its implementation discredited the liberal state. In 1973, as a result of federal intervention (black pressure to do so goes unmentioned), black workers long shunted into the dirtiest, most dangerous, and lowest paid work and seniority units gained the right to bump whites from jobs. The result was turmoil, but was relieved a year later as a result of a nation-wide consent decree from a federal judge in Alabama. As with neighborhoods, the only way blacks gained in the workplace came at the cost of their white counterparts. Expecting white workers not to resent this was expecting “a level of altruism seldom expected of others.” After this point “the streams of outright racism… flowed imperceptibly into a broader tide of resentment against government abrogation of individual rights and advancement by merit. The key is that whereas the former cannot be defended, the latter can.”

“The fact that Democrats, and the liberal state they built, undermined whites’ job security, local control over schools, and neighborhoods, and did nothing to stem the crime and cultural changes that threatened the family led workers to shift their allegiances to conservatism and ultimately the Republican party. For instance, in 1968, Wallace benefitted from whites’ resentment against the fall of segregation and from changes to seniority rights. Although the USWA backed the winner, the union was unable to convince many of its members to vote for their candidate. Because Wallace believed in states’ rights, and local control over schools and unions, and parents knew what was best for their children, “Wallace seemed to accord white working people the dignity and respect that other Democratic leaders had withdrawn.” The Alabama racialist and populist got almost two-thirds of the vote in white blue-collar wards in Baltimore. Wallace “tapped the reservoir of race, admixing only so much anti-communism, cultural nostalgia, and right-wing economics as necessary for effect.” The “power of the new social conservatism, then, came not from the alchemist’s wizardry, but from the long-term vitality of the populist impulse in American history. It also benefited, and still does today, from the fact that liberals —- civil rights leaders and historians among them — have so consistently underestimated it.”65

Durr faithfully describes the legitimate concerns of whites with this process, as white ethnics were left out in the cold by their Democratic Party.

“Durr argues that whites upheld segregated schools and neighborhoods, in large part because that was the basis for their community and culture. Many of his arguments go against the grain of scholastic conventional wisdom. He argues that working-class whites opposed blockbusting, whereby realtors broke a white block by selling a house to a black family because it was exploitative to black families who paid a premium for housing. Black families were manipulated and exploited by realtors who reaped the profits, and white workers often lost much of the value of the biggest financial and emotional investment they had made. Since African Americans paid a premium for housing, far in excess of its worth or often their ability to pay, many proved unable to maintain the older homes and the neighborhoods suffered decline. For white workers, the unwillingness of elected officials to preserve the quality of their neighborhoods did not lead them to anti-black violence, as in industrial cities in the North, but it did create “a dim realization that events in the city —- indeed, even events in their own neighborhoods — were beyond locals’ control.” More than that, it created the impression of “injustices perpetuated by an establishment that favored blacks at the expense of whites.”66

A party now totally captured by elites was intellectually incapable of coming to the defence of workers robbed of their right to communal exclusivity.

“The agenda of the liberal wing of the Democratic Party changed, while the "fundamental concerns of the urban working class" remained the same. Consequently, while blue-collarites retained their Democratic Party registration, they rejected the liberal Democratic nominees for state and national office who supported integration, busing, and the elimination of prayer in the schools by "nondemocratic — administrative and judicial as opposed to legislative" — means. They increasingly gave their support to conservative "populist" candidates who railed against an intrusive federal government and promised to reemphasize "those vital communities like the family, the neighborhood, the workplace.”67

Workers’ loyalty to the Democratic Party was not unconditional, and Republicans soon adapted to fill the vacuum left by liberalism.

Race War in Baltimore

“Confronted with the choice, the American people would choose the policeman’s truncheon over the anarchist’s bomb.”

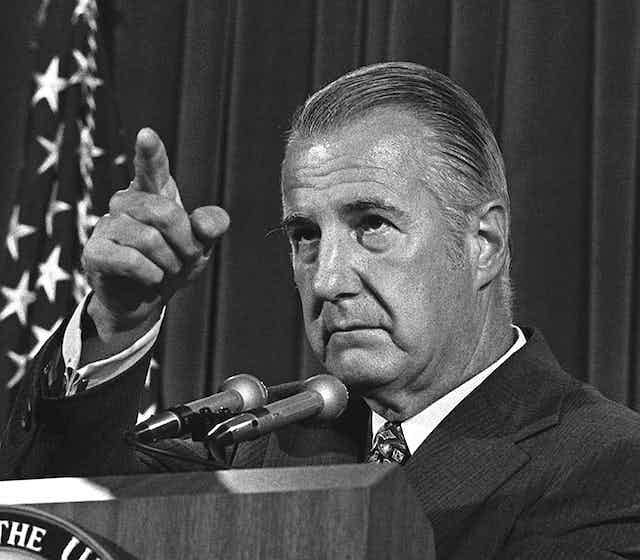

Spiro Agnew

Now to examine an electoral application of Durr’s model. My case study involves a son of Maryland. It is the meteoric rise of Spiro Agnew, a man who prefigured the Nixon ascendancy.

The 1966 Maryland gubernatorial race, a three-way contest between a Republican, a conservative segregationist Democrat and an independent liberal, anticipated the Nixon-Humphrey-Wallace race two years later.

George Mahoney, the Democrat, encouraged the police to adopt a “hit first, fire first” policy. His campaign slogan was “Your home is your castle; protect it.” The soon-to-be-governor Spiro Agnew was the relative moderate in the race, fittingly the Nixon to Mahoney’s Wallace.

But although he won on a moderate platform, the exigencies of the office demanded a conservative response.