“Must the morning always return?

Will the despotism of the earthly never cease?

Unholy activity consumes the angel-visit of the Night.”

Novalis, Hymnen an Die Nacht

This blog’s been a little dormant. I promise you all I’ve been hard at work with some top men on life’s important questions.

“The weariness that invades me sometimes in front of this mass of documents that I must interpret, comment on, systematize, before I dare to draw my major books from them. Perhaps this weariness is a warning signal.”1

While I jigsaw-piece together thousands of notes for future articles, here’s an account of what I got up to in East Germany over the summer.

Let’s look at what the German Right is doing right in Dresden.

Decamping from the Autobahn (and those speed limits only possible in a high-trust society), what hits you first about Dresden is its sooty skyline. Though I’m told the blackness of the buildings comes from the oxidization-prone Elbe sandstone, and not the famous firestorm, it can’t help but remind you of the war.

I’m not into militaria, and consequently am not really interested in the blood-and-guts of the European Civil War — and the attendant finger-pointing or victimology. What is encouraging is that, after decades of communist neglect, the reconstruction of Dresden is well underway. Animated by an unconscious faith that Germany can “stride on to new forms of glory.”

“We can rebuild cities again!.. Because everything can be rebuilt… and built beyond what even existed in the past.”2

I didn’t like the food. A heavy procession of pork and pilsners, showing me exactly why they needed amphetamines on the Ostfront. But frankly, I’d be more worried if it was good. Yes, Leipzig is dandy and Gorlitz (Koselleck’s birthplace) is picturesque. But what stuck with me was a chance encounter that certified Dresden as Germany’s most right-wing city.

In 2019, it was the only major metropole where the AfD received more votes than the other parties. Given its cultural prestige and wartime notoriety, Dresden serves as a hub for nationalist writers, thinkers and demonstrators. Though I arrived too early for PEGIDA season, and too late for the anniversary of the Dresden bombings, I did randomly stumble across the iceberg-tip of those networks. I won’t give too much away, but it was very inspiring, in spite of my interlocutors’ pessimism.

All and all, the holiday was an impetus for future research:

What history gave Dresden its unique political character?

And what lessons can we learn from the success of German nationalists at fostering real social capital?

A Short History of Civil Society:

When we talk about civil society, we’re talking about organizations that operate between the state and the market, from those dreaded NGOs to clubs and churches.

“Instead of appealing to a state authority to solve their problems, Americans founded an association, taking their lives into their own hands and working for the common good. For these reasons, freedom of association, even more than freedom of the press, was, for {Alexis de} Tocqueville, one of the most important political rights.”

As he correctly “considered human feelings and the process of their formation more significant for politics than rationally thought-out rights and interests,” Tocqueville recognized that the key to civilization was association. An unsocialized democratic society would inevitably degenerate into a tyranny unchallenged by the apathetic mass.

“I see an innumerable crowd of like and equal men who resolve on themselves without repose, procuring the small and vulgar pleasures with which they fill their souls. Each of them, withdrawn and apart, is like a stranger to the destiny of all the others… Above these an immense tutelary power is elevated, which alone takes charge of assuring their enjoyments and watching over their fate. It is absolute, detailed, regular, far seeing, and mild. It would resemble paternal power if, like that, it had for its object to prepare men for manhood; but on the contrary, it seeks only to keep them fixed irrevocably in childhood.”

Nietzscheans, in love with their own “solitude,” may revile such a suggestion. After all, their idol warned that “every association breeds vulgarity.” But nationalists have historically relied on civic institutions as supra-individual checks on a disloyal, imperial state:

“The rise of the ethnic nation as a political concept cannot be separated from liberalization and democratization, the two fundamental tendencies of the 1860s and 1870s. Historians have rightly argued that nineteenth-century nationalism was essentially a popular associational movement, and not only in Austria-Hungary but in all of continental Europe. National associations were less socially exclusive (even if they excluded workers) and promised, above all, more political participation.”

“The appeal to the nation in associations like the gymnastics clubs reveals, to the degree to which ‘sociable societies’ transformed into national societies, more about a country’s internal and external conflicts than an abstract common good… The global spread of associations and the circulation of the ideas and practices of sociability did not lead, as it was expected to by eighteenth-century practitioners of the Enlightenment, to a transnational moral sentiment of universal brotherhood and civility, but rather opened new social and political rifts.”

“The spread of voluntary associations democratized society and gave the previously excluded a place and a voice – but not necessarily a deeper belief in the liberal idea of a civil society.”3

That panoply of associations populating cultural life of the West disappeared over time. Reinhart Koselleck argued that these private associations took over the public state, and ran Europe into the ground with totalitarian, utopian schemes cooked up in their seventeenth-century wilderness years. Jürgen Habermas instead blamed the burgeoning culture industry, correspondent to a massified, industrial society swapping out a “critical publicity” for a “manipulative publicity.”

Is this where the story ends? The welfare state replacing mutual-aid societies? The mass-media usurping the role of the egalitarian salon? Civil-rights laws breaking ethnic labor-unions or fraternities?

Some semblance of a politicized civil society is not yet down for the count in Dresden. For its origin story, we must return to the dark ages of the DDR.

From Honecker to Höcke:

Was the DDR based?

A lot of right-wing guys, inspired by the works of Francis Parker Yockey, have argued this. The Prussian uniforms, man!

Sarcasm aside, we’re used to Tommy Sunic’s old syllogism, that “communism rots the body, and liberalism rots the soul.” The case study of Eastern Europe today broadly bears this out.

To completely grant this premise is, of course, to affirm the liberal idea that throwing money at a fascist problem solves it. They thought like this for two seconds, after Trump was elected, before committing to the current strategy of no-compromise and demographic-replacement.

In some cases, poverty shielded societies from progressivism. Modern mass-democracies could not have developed without “mass production and mass consumption” leading to a politics “predicated on hedonism and individual self-actualization.” Western European nations that overcame “perpetual scarcity” enjoy politics defined by the provision of “more and more material gratification to socially isolated individuals.”4

However, when you look at the statistics, AFD voters aren’t unusually poor5. Neither are Trump’s loyalists, as measured by surveys of January 6th attendees6.

East Germany is so reactionary today because Soviet Communism inoculated her from Anglo-America’s most potent psyops.

“The socialist state built its legitimacy on the myth of communist resistance against Nazism and a nationhood defined through class, local traditions and Heimat... As most GDR citizens were socialized by these memory politics aimed at a collective guilt-free memory it remains powerful to this day.”7

Their denazification was not based around the theories of the Frankfurt School’s finest, but the brute force of Stalinism, and the political exigencies of a state soon at war with Zionism.

“The consistent repression of an open discourse about Germany’s Nazi past, the exclusively socio-economic interpretation of fascism as a consequence of capitalism, and the ‘logically’ following constant denial of any continuity between the Nazi past and the GDR present, including the denial of any responsibility for the crimes of the past, amounted to the dogma of an ‘anti-fascism by decree’… rather than a truly anti-fascist education of the GDR’s population.”

“As a consequence, East Germans lacked substantial information about the Nazi past, while interest in this part of German history increased and mixed with sympathetic curiosity. For example, in 1988, 12% of East German high school students and 15% of East German apprentices agreed with the statement that fascism also had its good side.”

“The quantité negligeable of foreigners in the GDR, racism, as well as an ‘anti-Semitism without Jews’, were composite elements of an authoritarian culture that prohibited an open and self-educating discourse on these matters.”8

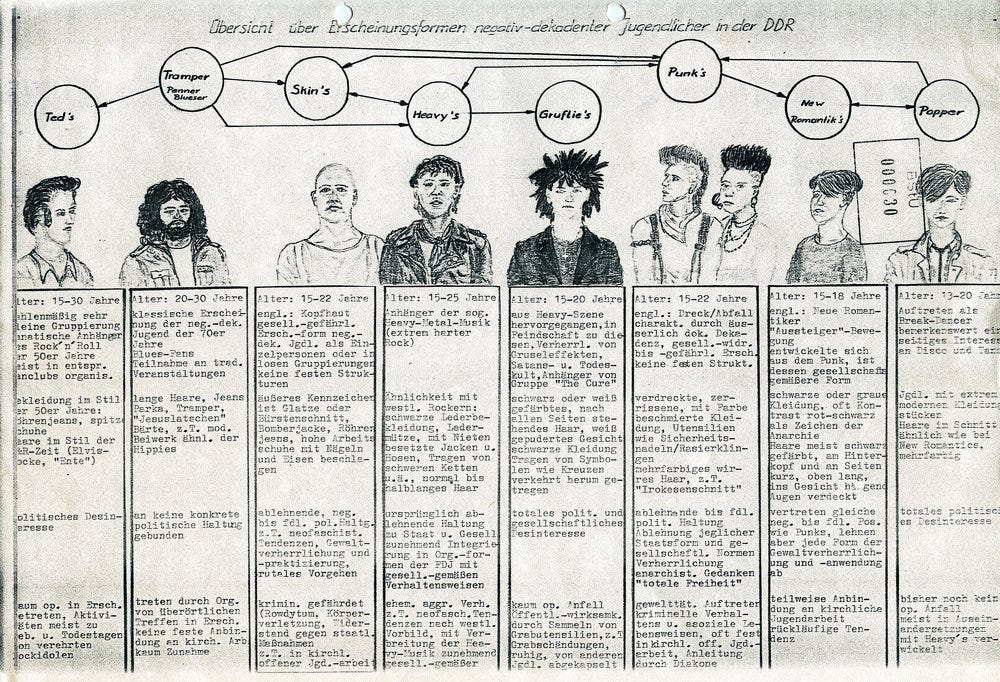

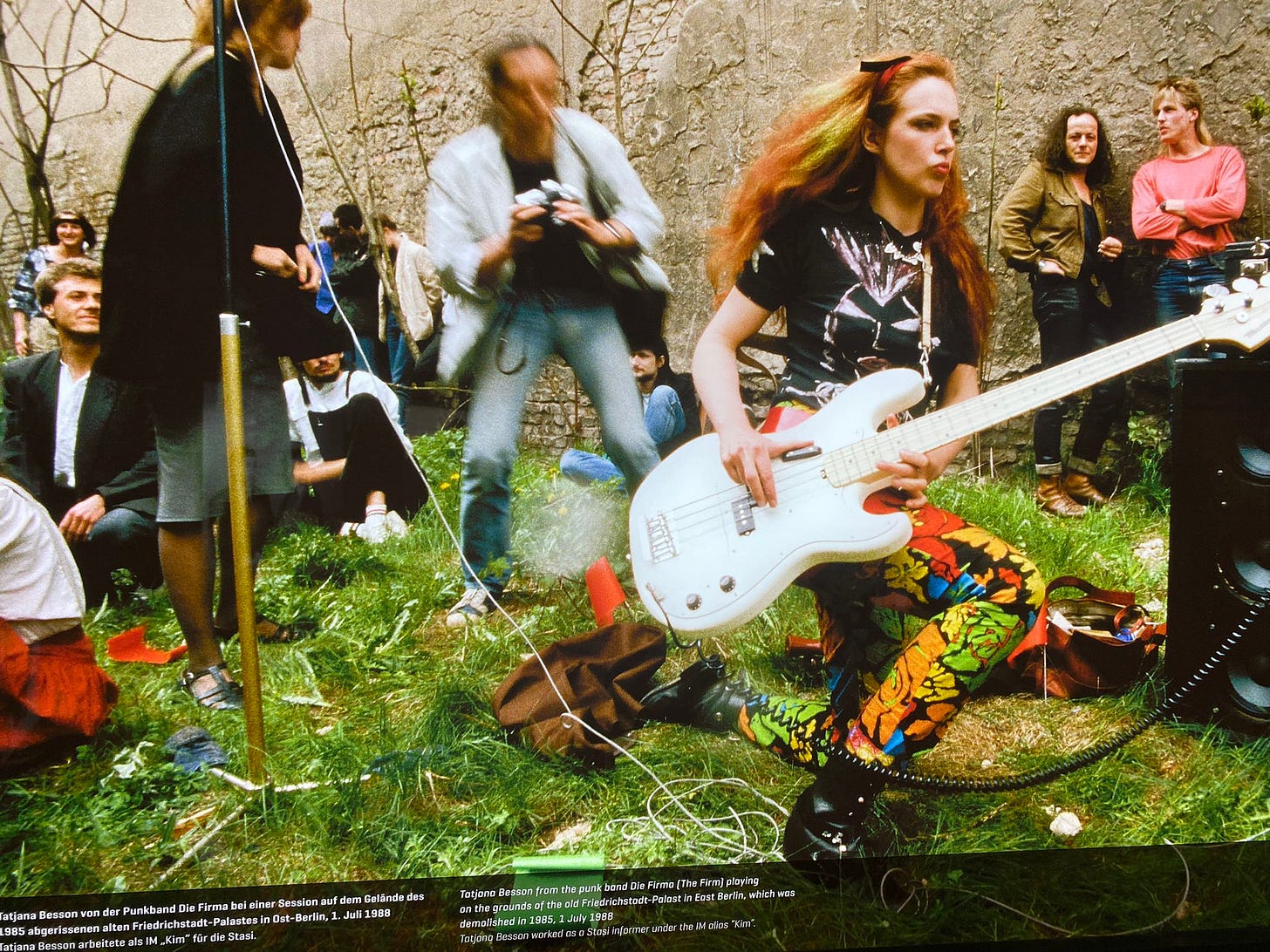

That all being said, my understanding is that yesterday’s punk rockers are today’s AFD voters. Those who rocked against communism when and where it really counted.

It’s just for the best that they dialectically absorbed the most sober sensibilities of their regime.

Celebrating the internal enemies of East Germany does not mean that the Bundesrepublik was “based” either. In the words of an old mutual, the BRD “functioned best as a giant pirate ship, with a foreign policy literally conducted by businessmen, freed from world-historical responsibility to roam the happy hunting grounds of selling high-tech capital goods to the communists.”

The Historikerstreit, to be EXTENSIVELY covered in a future article, showed a bit of nationalism was left in West Germany’s civic culture. But that is a story for another time. In any case, the situation in both states was complicated. My overall argument is that 1945 was not a stunde null for German culture, and history’s contingent contexts afford the West second chances, even now.

“The early FRG equally lacked a critical assessment of Nazism, even if a unified state policy like that in the GDR was absent. National belonging was not constructed by referring to the past but by focusing on economic strength and Europe. Not until the 1960s did a generational shift and legislative and societal debates lead to critical assessment of the past. In the 1980s, this critical memory culture reached a broader social basis through citizens’ initiatives facilitating a consensus on collective Holocaust memory as the absolute referent ‘from which notions of political belonging could be thought anew.’”9

For this article, just remember that the voters who are right-wing today cut their teeth resisting the commies.

Bohemians, Against a New Bautzen:

Cliché liberal accounts of civil society lament its decline, seeing the resultant social atomization as a precondition for Fascism. But new research shows that places with high levels of social capital preserve a patriotic sensibility.

Here’s John Ganz aggregating good sources on the matter:

This means that YOU, Anon, must touch grass and try to find OUR PEOPLE in meatspace. But let’s look at an example of nationalists doing it right.

Here is where Dresden inspires, practically demonstrating “the importance of local socio-cultural milieus for… nativism beyond the grassroots level.”

The most insightful academic article on the Dresden scene zeroes in on Susanne Dagen’s bookshop, its nationalists drawing sustenance from the past while developing a positive vision for the future. Where nostalgia is not simply “the pain from an old wound,” but “a tool for political mobilisation, not of the fearful left-behind, but of an educated bourgeoisie engaged in a hopeful activism for a nativist future.”

“Politicization relies on the merging of two forms of nostalgia… a positive nostalgia for a guilt-free past… ingrained in the self-understanding of the East German Democratic Republic (GDR)… {and} a negative nostalgia characterized not by a celebration of the GDR, but of the resistance to it.”

Ostalgie is a cozy alternative to the post-1980s “Holocaust-centred collective memory” of the Western world, and the memory of the anti-communist struggle provides for an rightist but non-fascistic point of reference.

Aesthetically old-fashioned, Dagen’s bookstore is designed as a place where one can “step back from the hectic every day, resist the Zeitgeist and gain strength to face contemporary challenges by reading.”

“It serves as an alternative space for political discussions and informal meetings to plan projects. It prefigures a far-right future based on ‘community, solidarity, the celebration of German culture and politics that focus not on economic profit in the present but the future of German culture’.”

The construction of a real-life “free space seemingly untouched by the state,” demands the “cultural Bildung (education) necessary to survive in ‘today’s profit-driven system’.”

Growing up “in the universe of Dresden’s 1980s subversive subculture,” Dagen’s non-conformist model remains the “‘bohemian biotope’ for utopias and alternative lifestyles that formed” under communist rule.

“The traumatic experience in the late GDR is contrasted with the feeling of community in the artist colony, the nostalgic memory of which is selectively used to interpret the present situation. Today, Dagen sees censorship and a disappearing of ‘places of true community’.”

Crucially, these artists’ colonies portrayed themselves as apolitical, even if they imbibed in bourgeois practices that challenged the socialist state’s symbolism.

“I was never a political person. After the end of the GDR we were all just tired of politics. In the GDR politics were everywhere.”

Today Dagen appeals to a politics “politics informed by culture, not merely based on competence,” to “be confident of our roots, to face the future and save Germany before it disappears.”

That remains her hope, “to topple a system a second time.”

Dresden’s rambunctious, Cold-War scene served as a ready-made infrastructure for nationalist activism. These “well-established East German social repertoires of protest and common political networks… transcend the left-right divide and impact German national politics,” helping in the intellectual legitimisation of their dissident-right.

In the article, Dagen hosts Vera Lengsfeld, a Greenie turned Christian Democrat10 hocking a book on East Germany’s peaceful revolution. In their eyes, today’s “‘left-liberal totalitarianism’… is not far from 1989.”

“Look at the denial of reality by the established parties. Their discourse on immigration reminds me of the wishful thinking of the GDR’s political leadership. Reality and the mood in the country are simply neglected”

“We all have been through this before. Being pressured by the state, having to risk one’s existence because of what one says.”

Only today, the left exerts censorious pressure not only through the state, but through the influence of civil-society groups like Antifa. A corporeal redoubt for the right, Dagen’s scene exists to counterbalance that, refurbishing the German historical-consciousness.

Is it over? Are we back?

The Germans have answered that with their history of eternal becoming.

“It is a prefigurative nostalgia that draws on past resistance and solidarity to enact in their activism the culture-driven, nativist politics they hope for. The coexistence of this utopian nostalgia with a dystopian future shows that hope and anxiety are not necessarily antagonistic but complementary. Instead of seeing nostalgia as a monodirectional and fearful past-fixated reaction to change, the activism of such local intellectuals is better understood in terms of ‘anxious hope’ – a hope driven by dystopian visions of a multicultural future and the belief that it is not too late to act.”

One hears echoes of Gramsci’s “pessimism of the intellect,” paired with an “optimism of the will.”

“Not a simple glorification or appropriation of the past by the fearful left-behind but the basis for a hopeful far-right activism for an alternative, guiltfree future.”11

Ave AFD!

The nationalists I spoke to said they were surprised that Merkel, a little “East German girl” made it to the chancellery. Of course, she betrayed them, getting us to where we lay our scene.

The AFD takes 20% of the national popular vote as of the time I write this. They hold outright leads in East Germany. Having taken the lead in Saxony-Anhalt days ago, that state party has been classified as a “right-wing extremist” organization, alongside the Thuringia outfit.

Only one party stands against Germany’s present victimization at the hands of Islamic or American terror attacks. The central issue is German, and by extension European sovereignty. Germany cannot remain an “economic giant and political dwarf.” Particularly if America continues its leftward course, exporting its foul culture as it implodes.

If it survives, it will be by virtue of the East’s political culture.

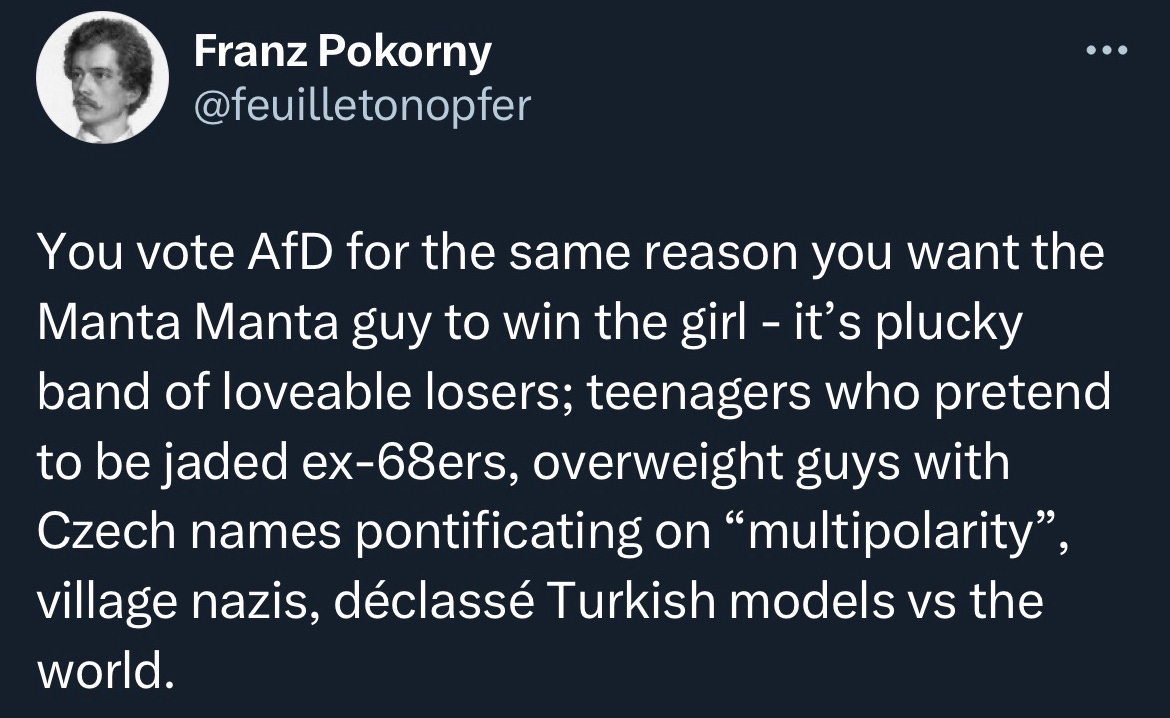

The voters may not be our guys yet12, but they don’t have to be. Because of all of this cultural infrastructure, the AFD’s leaders are well-versed in New Right literature.

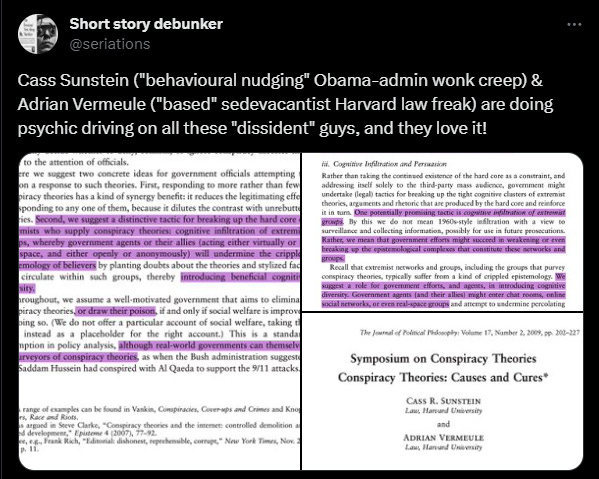

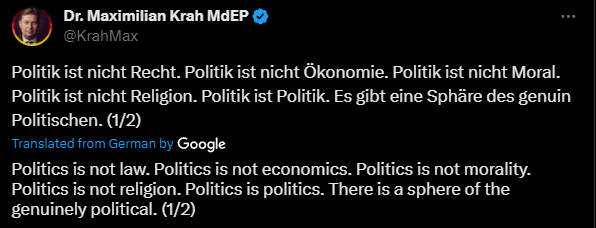

Max Krah is a legitimate Schmittian, and not in a gay, Adrian Vermule kind of way. He will lead the AFD in the 2024 campaign.

Björn Höcke is a historicist right-winger after my own heart — there is simply too much good stuff in his book to unpack here.

Born to Prussian expellees transplanted into the Rhineland; this is a guy who hangs Friedrich's Wanderer above the Sea of Fog over his fireplace. He knows what he’s doing.

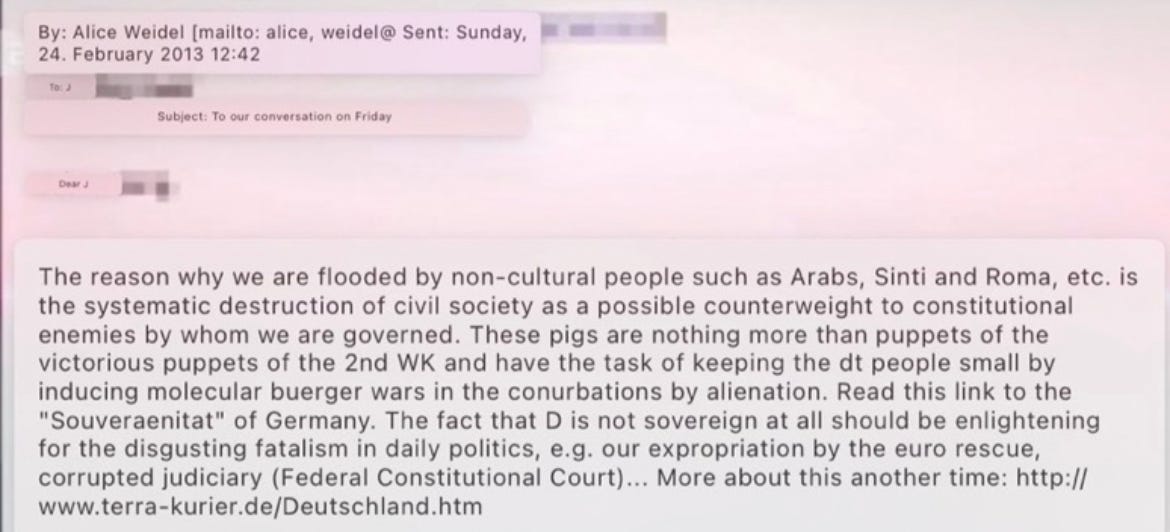

Fresh from the experience of expatriatism as Goldman-Sachs’s girl in China13, Alice Wiedel may be in a lesbian relationship with some Sri Lankan woman, but when the chips are down, she stands by her man:

Not enough for you? Here are the leaked emails:

Basically, trust the plan.

Wiedergeburt der Öffentlichkeit:

Progressing from the digital-archipelago to real-life civic associations is the next step for western nationalists.

“The mechanisms of ideological terror that Koselleck sees find their typical users not on the left, but on the right of center…. Through the secret society, the supposedly rational state philosophy of the Enlightenment escalates into a diffuse conspiracy religion that operates from anonymity. A lot connects the men's association lodges and their candlelight rituals with the fantasists of the 21st century.

Identitarian groups and Reichsbürger gangs are also hiding out. Preferably on social networks, where you remain as unrecognized as in the vaults of the Freemasons. From YouTube to Telegram to Twitter, brown-bots are spreading diffuse fears of corona dictatorship, eco-Stalinism or population exchange. The vanishing point of all these strategies is exactly what Koselleck lucidly described - the discursive creation of crises. Germany should believe that things are bad for them. Because, as a former AfD spokesman once openly admitted, that was good for right-wing populists.”14

The pundits’ fear of frogtwitter is justified, but the AFD ascendancy would not have happened if not for places like Dresden and their scene.

“Implicit in enlightened ideas and practices – the belief in a connection between virtue and sociability.”15

For this reason, the social space between man and state will cop more and more scrutiny from the powers that be and their deputies.

“It is the natural ambition of the power holder to cast a criminal light on legal resistance and even non-acceptance of its demands, and this aim gives rise to specialized branches in the use of force and the related propaganda. One tactic is to place the common criminal on a higher level than the man who resists their purposes.”16

These German patriots, a leaderless resistance carrying forth the torch of their nation under the harshest conditions, are an inspiration to us all.

“When all institutions have become equivocal or even disreputable... moral responsibility passes into the hands of individuals, or, more accurately, into the hands of any still unbroken individuals.”17

You don’t necessarily have to read this Ernst Jünger line as foreshadowing the hippie-libertarianism of his later career. The point is that one ought not to travel the Forest Passage alone.

Your salvation lies in “individuals and free men,” against the faceless “numbers”18 of the state. Your faith in the conspiracies of real people, concrete orders and individuals. The hope of a peaceful revolution, when all is breaking down around you. Shadow societies and governments in waiting, prepared for a popular mandate when it comes.

As for the Germans, I’ll finish with choice quotes from Björn Höcke’s book. More than a mere poundshop Hitler, he captures his volk’s eclectic spirit the way only a history-teacher on our side of things can:

“The example of Luther shows: revolts and uprisings never happen among us Germans for their own sake, they only flare up when there is persistent injustice, dishonesty and incompetence in leading classes. In contrast to some other peoples, we are not rebellious by nature… and are generally regarded as “submissive to the authorities”…

“Think of Arminius’s fight for freedom against the Roman Empire, or the struggle of the Staufer emperors against the worldly arrogance of the popes, the peasant revolt in the 16th century, the wars of liberation against Napoleon, the patriotic resistance against Hitler, the national uprising on June 17 against the Soviet occupying power, the aforementioned German autumn of 1989 and today the civil protests against the immigration policy… The popular view that we Germans are eternally naïve idiots who would dully accept all the demands of the ruling classes certainly does not correspond to historical reality.”

“At some point our patience will run out, too, and then the legendary “Furor teutonicus” will break out, which the ancient Romans trembled at.”

“Herein also lies my basic confidence and composure… No mater how dire things get, there will eventually be enough of our people to start a new chapter in our history. Even if we will unfortunately lose a few parts of the people who are too weak or unwilling to resist the ongoing Africanization, Orientalization and Islamization. But apart from this possible bloodletting, we Germans have historically shown an extraordinary ability to renovate after dramatic declines. Think of the Thirty Years’ War or the collapse of 1945. Whether we will make it again is not certain, but there is legitimate hope for renewal…

Yes, the run-down German house needs extensive renovations. A few corrections and reforms will not suffice. But German absoluteness will be the guarantee that we will tackle the matter thoroughly and fundamentally…

Once the turning point has come, we Germans won’t do things by halves. Then the rubble heaps of modernity will be cleared away.”19

Für B.W. I hope you’re wrong about your countrymen’s moral courage.

Mircea Eliade, No Souvenirs: Journal, 1957-1969

Jonathan Bowden, Credo

Above quotations all from Stefan-Ludwig Hoffmann’s superb Civil Society, 1750-1914

Paul Gottfried, After Liberalism

“We find that AfD voters were not driven by anxiety about their own economic situation: they are no ‘losers of globalisation.’ Instead, AfD voters in 2017 were driven solely by two factors: their attitudes towards immigrants/refugees and anti-establishment sentiment/satisfaction with democracy in Germany.”

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09644008.2018.1509312

https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/01/06/trump-capitol-insurrection-january-6-insurrectionists-great-replacement-white-nationalism/

Julian Göpffarth, “Activating the socialist past for a nativist future: far-right intellectuals and the prefigurative power of multidirectional nostalgia in Dresden”

Michael Minkenberg, “German Unification and the Continuity of Discontinuities: Cultural Change and the Far Right in East and West”

Julian Göpffarth, “Activating the socialist past for a nativist future: far-right intellectuals and the prefigurative power of multidirectional nostalgia in Dresden”

Her second husband was a Stasi informant, and didn’t tell her until 1992. That’ll radicalize you!

“He later explained to her that he, as a Jew, supported the GDR since he saw it as a response to Auschwitz.”

All quotes from the section are from Julian Göpffarth’s “Activating the socialist past for a nativist future: far-right intellectuals and the prefigurative power of multidirectional nostalgia in Dresden”

https://hubertus-knabe.de/wird-deutschland-rechtsextrem/

…Let he who is without sin, etc etc…

https://www.nd-aktuell.de/artikel/1172585.unruhe-und-arroganz-lange-lebe-die-krise.html

Stefan-Ludwig Hoffmann, Civil Society, 1750-1914

Ernst Jünger, The Forest Passage

Ibid

Ernst Jünger, Eumeswil

Björn Höcke, Nie zweimal in denselben Fluß: Björn Höcke im Gespräch mit Sebastian Hennig