“The premier demand upon all education is that Auschwitz not happen again…. Every debate about the ideals of education is trivial and inconsequential compared to this single ideal: never again Auschwitz. It was the barbarism all education strives against. One speaks of the threat of a relapse into barbarism. But it is not a threat — Auschwitz was this relapse, and barbarism continues as long as the fundamental conditions that favoured that relapse continue largely unchanged.”

“Education After Auschwitz”, Theodor Adorno

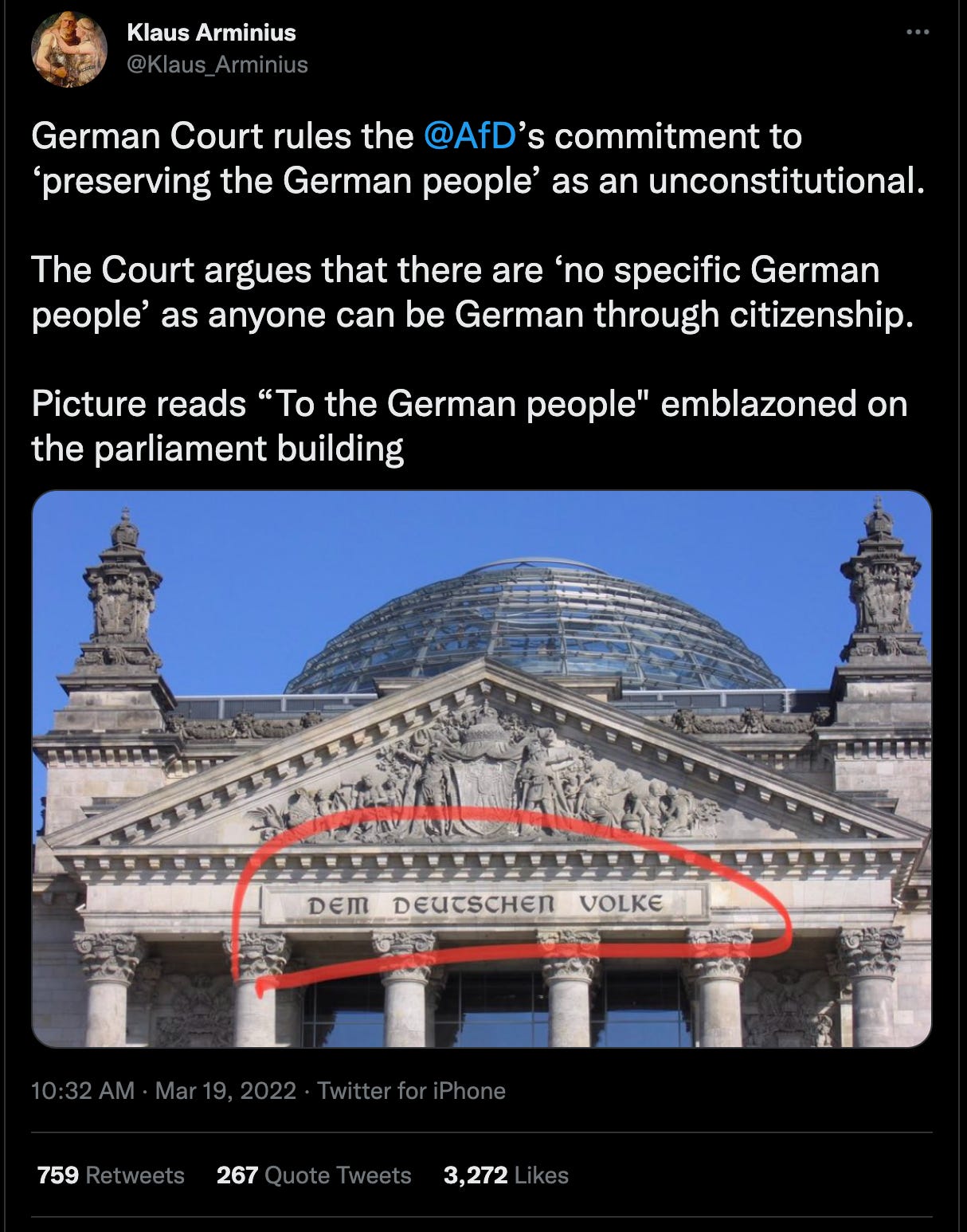

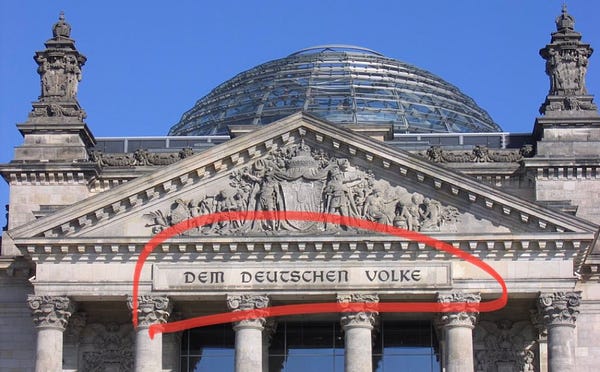

From a nationalist perspective, modern Germany certainly appears to be the end stage of the social-progressivist’s project. The political system is centrist and managerial. As far as high culture goes, the country retreats from taboo nationalism and, in the place of teutonic chauvinism, embraces diversity, equality and genuflectory historical guilt as unqualified goods. The state is no longer governed in the interests of “Dem Deutschen Volke,” as is written on the Reichstag.

Observing the triumph of managed mass-democracy, foreign forms of multiculturalism and, with some exceptions, a fealty to the American Empire in Central Europe, one naturally questions how such radical changes were able to be institutionalised in Germany without an equally radical reaction. The answer lies in the shortcomings of the postwar German right, which like other forms of Western Conservatism, failed to conserve anything.

Since 1945’s “stunde null” (zero hour), conservatism in Germany shaped out to be a spent force. External limitations regulating their political project were there from the start. How is it possible to even be a reactionary in a country encouraged by all to engage in a persistent overcoming of the past (Vergangenheitsbewältigung)2 - the past a conservative must by definition defend? Complicating this conservative task is the grand historical concept of the Sonderweg (special path), a historiographical meta-narrative suggesting that Germany’s passage to modernity was distinct from the paths traveled by other European nations. That narrative originally served to glorify particularist German greatness from a mystical, aristocratic, conservative perspective. As the philosopher Panagiotis Kondylis puts it:

“Here the "German idea" could be portrayed as the ideal union of the warrior and of the thinker, which counters the Western "ideal of the trader" and is far superior to this Western ideal. The German "special way" accordingly by-passed this "trader" as well as the entire "shallow" Western Enlightenment whose alleged narrow-minded rationality supported the worldview of the "trader".”3

Germans conceived of themselves as a special country situated between western progressivism and eastern reaction. Erudite and proudly continental.

The hitherto dominant narrative of national excellence and exceptionalism propagated through the Wilhelmine, Weimar and Waffen-SS eras of German history was flipped on its head after the war. All history before 1945, excepting the Weimar era, came to be depicted as a dark age of reaction before the Germans were saved from their naturally despotic urges by American psychologists and Communist Commissars.

The brutal excesses of the Nazi moment were read by progressives as the culmination of German history rather than an aberration from it. Progressive academics drew a straight line from Herder to Hitler. This now-dominant portrayal of old Germany as a nation with an exceptionally negative impact on the world was essential to the postwar project of national re-education. In Kondylis’ words:

“A negative "Western" version opposed the extended positive German version of the German "special way"... The negative evaluation of the "special way" appeared in the Anglo-Saxon and French war propaganda since 1914 with the claim to an interpretation going a long way back (in time) of a terrible or dreadful state of affairs in Germany, in order to be constituted after 1933 as a regular systematic construction, which was supposed to make clear the fateful course of German history from Luther to Hitler via Friedrich the Great and Bismarck. It is certainly no coincidence that the long and rich history of ideas of this construction has not so far been the object of in-depth investigation, although the topic is extremely explosive: scientific insight into the circumstances surrounding this construction's formation or its polemical-ideological character - to say nothing of its manifold spitefulness - would inevitably exert disruptive effects on "re-education", which was, in terms of content, based not least on this construction.”4

The consequence of this historical narrative was the condemnation of an entire nation’s past. Over time, the very notion of holding pride in belonging to an exclusive national community bound together by shared blood and history was thrown into doubt. A Nietzschean idea of the eternal recurrence of barbarous Fascism following the predetermined failures of a 19th-century bourgeois society dogged the thought of socially-concerned Marxists like Adorno. They committed themselves to blocking off any paths to the return of that older state of affairs, fearing that such a society would inevitably lead to a redux of Auschwitz5. In response to this fear they perceived, organisations like the Frankfurt School, empowered by the resources of the American state and the approval of the American academy, set about psychologically turning people away from the “repressive” and “authoritarian” norms of prewar Europe.

With a history condemned, and parallel mental and political reconstructions of the German character underway in both the Eastern and Western blocs all through the Cold War, German rightists of all stripes had little to work with when constructing a worldview capable of polemically weathering the winds of change brought forth by British brains, American brawn, and Russian blood. With national self-determination now a distant dream, they were subsumed into an anti-communist formula under the aegis of NATO - in Lord Ismay’s words, designed “to keep the Soviet Union out, the Americans in, and the Germans down.” Like their newfound fusionist allies across the Atlantic, German conservatives opposed the immediate threat of communism in an alliance with liberal capitalists - who became the senior partners in this purely political marriage. A formula of anti-totalitarianism was invented in the Adenauer era, which would have a lasting effect on the conservative European’s psyche, now captured by a uniquely Anglo-American flavour of tyrannophobia like never before.

Paul Gottfried describes this anti-fascist, anti-communist, liberal-conservative worldview as “an intellectually fortified campaign against totalitarianism…anchored in a prewar, liberal bourgeois outlook… focused on the overlaps between Nazi and communist practices. The anti-totalitarians thought they were defending a constitutional order that incorporated Christian moral teachings and maintained non-state controlled spheres of individual autonomy and corporate authority.”6 In practice, this was the philosophy of the new CDU, which aligned nicely with the postwar constitution of the Buckleyite GOP and the British Tory party.7

As in the Thirty Years War, a divided Germany functioned as the European battleground for competing faiths.

The question of who walked the deutscher dog in those years further illustrates my point about the intellectual poverty of the postwar German Right. Mouth-breathing Marxists will point to Nazis with prominent postwar roles in NATO and NASA and schemes like Operation Gladio to justify their cockamamie Leninist belief that Fascism is nothing but capitalism in decay. To those types the Nazi-Soviet war continued after 1945 under a new guise.

This distorts reality.

It is true that, as both are on the right in the European context, former fascists and liberal capitalists collaborated in the battle against the USSR following the Second World War. What one must remember is how the latter faction consistently dominated the former in their Cold War tryst. There was collaboration with the allied regime on the bureaucratic level - inevitable given the totalitarian omnipotence of the Nazi state and the quality of their officials - but the idea that these Cold War alliances of expediency reflected crypto-Nazism influencing the ideology of western liberalism is an absurd communist canard.

It was an alliance of convenience, and as seen from the leftward drift of all European societies since the war, the faction further to the right never dominated the relationship. As the Azov Batallion over in Ukraine is staring to realise, the fascistic allies of western liberalism will be discarded as soon as they are no longer useful to the Globalist American Empire. Postwar, all other rightist forms were purged in favour of a liberal fusionism, which explains the decades-long absence of intellectual nationalism from the European discourse.

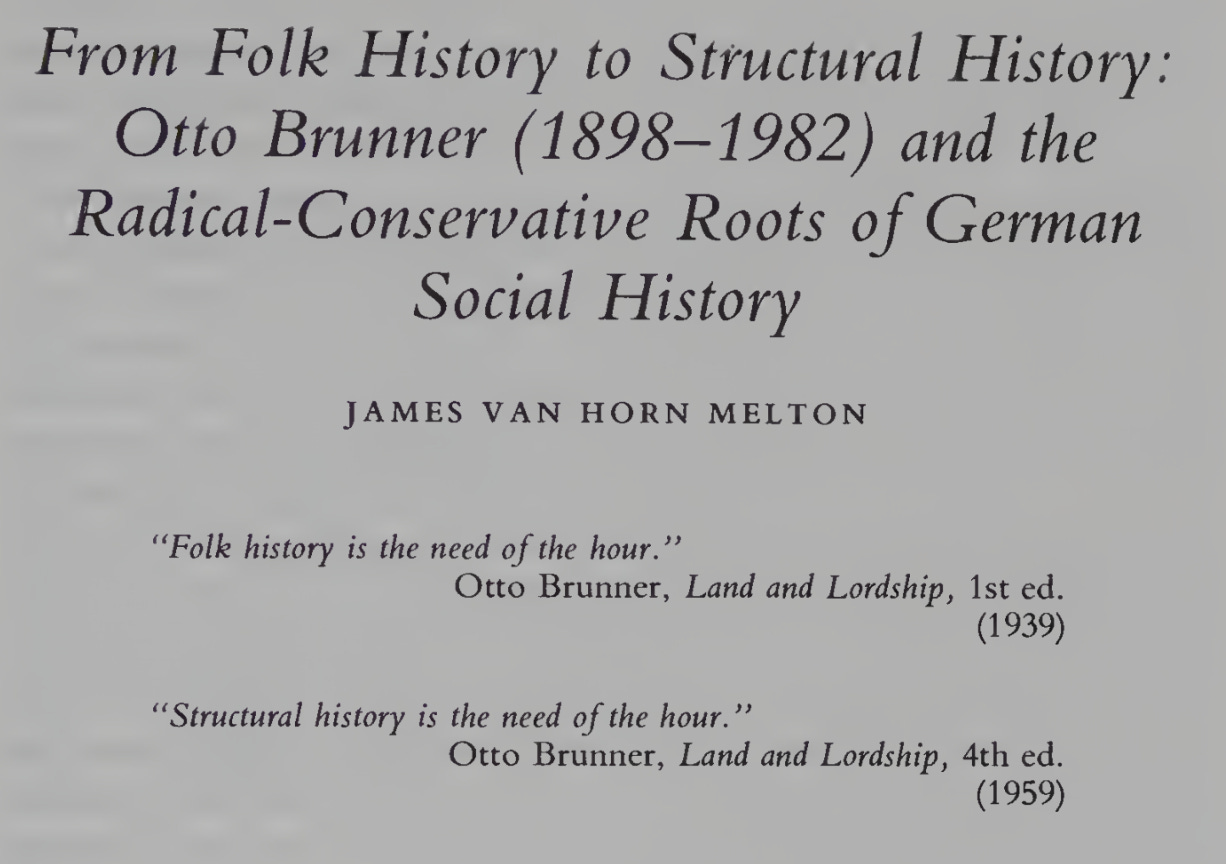

Several unreconstructed National Socialist intellectuals survived the war years in ignominy. One needs only to observe Martin Heidegger hiding in his Black Forest cabin, Carl Schmitt lecturing in Francoist Spain, or Otto Brunner removing pro-Nazi segments from his “Land and Lordship” - inventing social history as “the need of the hour,” and shifting from 1939’s Volkisch History to 1959’s “Structural History”.8

In a 1949 letter to the nationalist philosopher Ernst Jünger, Martin Heidegger reassured his withdrawn friend “that to endure solitude is not an escape but the highest freedom.” In reference to their covert intellectual communion, he repeated a note of Nietzsche’s: “Venice is formed by a hundred profound solitudes together - that is her magic. An image of the man of the future.” Heidegger viewed the aphorism as containing “a law for future poets and thinkers… for whose preparatory practice we are perhaps appointed.”9

In similar tones, Carl Schmitt declared that the old Conservative Revolutionaries of Weimar “had been put out to pasture.” To Schmitt, his old polemical comrades now resembled “domestic animals who enjoy the benefits of the closed field {they were} allotted. Space is conquered. The borders are fixed. There is nothing more to discover. It is the reign of the status quo…”10 They withdrew from overtly political pursuits and devoted themselves to more philosophical questions.

These anecdotes are offered not to praise Nazism but to show it buried. Indeed, not all of the aforementioned thinkers were as taken in by the “inner truth and greatness” of Nazi ideology as Martin Heidegger was. We see these tensions reflected in Carl Schmitt’s polemical duels with the National Socialist Otto Koellreutter and Otto Brunner’s protection of the Jewish Erich Zöllner from deportation, in spite of his intellectual affinity for Nazism’s volkisch critique of the 19th-century Rechtsstaat.11 These examples reveal the profound change in Germany’s metapolitical orientation following the occupation years, and the consequent political unviability of any non-fusionist, traditionalist Right-Wing movement in those circumstances.

In light of these myriad, externally imposed limitations, the German scene failed to develop a politically viable right-wing movement capable of challenging the liberal priors of the postwar world order. As the project of removing western men and their governments from historical or ethnic contexts advanced, the makeshift postwar right in Germany seemed only capable of holding actions and limited reactions. They never drove the course of the political conversation except when it was useful for the Amerikaner Cold Warrior masters of the West German state. Barring some symbolic gestures on the part of Helmut Kohl, the “Wende nach rechts” (turn to the Right) anticipated by unreconstructed traditionalists never took place, notwithstanding the CDU’s promises, even following electoral triumphs and an ultimate victory in the Cold War.

This story may sound familiar to American conservatives, who are likewise used to winning elections and losing culture wars. Forces of the Right in both nations are enslaved to anti-national, anti-conservative formulas that deal with abstract ideas rather than the protection of specific groups in specific historical situations. They are ateleological movements devoted to the protection of mere mechanisms of government, who have long since forgotten the ends for which such ordinances were drafted.

On one side of the Atlantic, the words “all men are created equal” were taken out of context to justify an oxymoronic “proposition nation.” On the other side of the pond, Germans, humbled by battle, were made to accept “constitutional patriotism” and “democratic values” as the substance of their postwar identity, flying in the face of the historical and ethnic character of the German nation. Ephemeral “democratic” values determined by the liberal power centres of society proved to be flawed foundations for a meaningfully conservative ideology.

There are also unique structural limitations imposed on the German dissident right, structural limitations designed to curtail right-wing political action that are built into the postwar system, in light of what happened last time. Attempts to escape the Overton window will be dogged by the Verfassungsschutz, an “agency for protecting the constitution” which reserves the right of infiltration - credibly accused of planting evidence on fringe parties12. Such modern-day radicals will also have to preach their message to a population most severely afflicted by the paralysing guilt now familiar to most western peoples. This infrastructure was allowed to be developed in the wake of the Second European Civil War, and all who dared to challenge the zeitgeist of guilt were pushed from polite conversation.

It falls to other rightist men of the west to study the shortcomings of the German Right since the war, itemising their theoretical missteps and practical failures in avoidance of their tragic fate. Such examinations are crucial for avoiding submission to non-right ideologies, which will finally allow the aspiring traditionalists, conservatives, libertarians and nationalists of the west to emancipate themselves from the postwar paradigms of progressivism.

"There's sort of a sick mentality that says that generations after generations must atone sins of what happened in 13 years of German history and ignore the other 1,500 years of Germany," dissident military expert Douglas MacGregor says. "And Germany played a critical role in central Europe in terms of defending the serving Western civilisation. So I think that's, that's the problem."

https://edition.cnn.com/2020/08/07/politics/jewish-advocacy-groups-decry-german-ambassador/index.html

https://www.panagiotiskondylis.com/the-german-sonderweg.php

Ibid

Read “Minima Moralia” for more

See Gottfried: “How European Nations End” https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0030438705000414

This is where the modern conservative’s antipathy towards using power to help his friends comes from

See the superb “Paths of Continuity: Central European Historiography from 1930s to the 1950s” edited by Hartmut Lehmann and James Van Horn Melton

See “Correspondence 1949-1975: Martin Heidegger and Ernst Jünger”

https://counter-currents.com/2011/07/the-lesson-of-carl-schmitt/

“See Zöllner's appreciative reflection in his obituary for Brunner in the Mitteilungen des Instituts für österreichische Geschichtsforschung, vol. 90 (1982), p. 522.” From https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Otto_Brunner#cite_note-4

See Gottfried: “How European Nations End” https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0030438705000414